Can nature make us happier, healthier and more creative? The simple answer is yes, . . . and it’s been scientifically proven. In Season 6, Episode 10, hosts Sarah Thorne and Jeff King, Lead of the Engineering With Nature® Program, US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), welcome Florence Williams, a renowned journalist, author, speaker, and podcaster who spent over three years traveling around the world talking with leading scientists about how to quantify the benefits of nature on people’s health and well-being. Florence joins us to talk about her book, The Nature Fix: Why Nature Makes Us Happier, Healthier, and More Creative, and what she has learned on her journey.

As a contributing editor for Outside Magazine, Florence is sometimes assigned stories; but when she was asked to write about the science behind why we feel good in nature, the assignment immediately spoke to her: “I had just moved From the Rocky Mountains, where I had lived for 23 years, to Washington, DC. Although I grew up on the East Coast, the move to DC still felt like a really jarring shift in my psyche after living in the mountains for so long. I was thinking a lot about what I had lost in my daily nature connection.” What started out as a magazine story ended up as a book: “I realized that there was a lot of science happening at that very moment—in some ways a turning point in the science, with lot of new technology enabling different kinds of field experiments, for example, with neuroscience.”

In writing The Nature Fix, Florence was motivated by what she calls our “epidemic dislocation from the outdoors,” which involves the shift to moving to cities and simply spending less time outside. “I believe we’re living in the largest mass migration in human history, that is the shift to indoors.” She notes that children today spend significantly less time outside compared to their parents when they were growing up, who themselves spent less time outside than their parents’ generation. “We aren’t really paying attention to what that might mean for our emotional health and for our physical health.”

Florence notes the growing volume of scientific study, of various sorts, regarding nature’s effects on health and well-being. Some studies use electroencephalography and neuroimaging to observe people’s brain activity while walking in nature. There are also large-scale epidemiological studies and public health studies that look at the health of people based on where they live. And there are smaller-scale psychological studies of people in recovery or with certain health conditions that measure the effect of nature-based treatments such as horticultural therapy. “On many scales, this is data coming in. It’s very hard to prove cause and effect, but it’s a lot of suggestive data. There’s a ton of mounting evidence. When you consider all these different scales and types of studies, it becomes really, really powerful.”

Florence likes to “witness the science”, as she says, “sometimes participating in it as a way to tell the story.” The first stop on her journey to learn about the benefits of nature was Japan, where a physiological anthropologist, Yoshifumi Miyazaki has been studying “forest bathing” for years. Florence explains “forest bathing is the idea of being in a nature space, almost like sunbathing, in that it’s a kind of passive reception of stimuli from nature, especially engaging the senses.” She notes that after just 15 minutes of sitting in the woods or walking around trails there are significant positive physiological changes on metrics like blood pressure, respiration, heart rate, and hormone levels. “In Japan there are dozens of so-called ‘forest therapy facilities’. You can go on these trails with designated forest therapy rangers who facilitate a sort of opening of the senses. It’s a way to be really present and mindful in these spaces. It was remarkable to me that these changes happened after 15 minutes.”

Florence notes the importance of “place” and how there are many different habitats that people can choose from to get their nature fix. “For me, I love trees and I love the forest, but not everyone does. Some people feel claustrophobic in a forest, or they feel unsafe. They may prefer being on the beach. Other people say, ‘I don’t really like nature, but I really like gardening.’ I think we have this idea in our culture that nature means you’re in a wilderness, or on a trail without other people around, or you’re on some pristine mountaintop. There’s a lot of variability in people’s preferences for nature and I think that in general, we are not very good at forecasting how a particular nature setting will make us feel.”

On another stop on her journey, Florence met with David Strayer, a cognitive neuroscientist, who is interested in creativity and how people come up with ideas. He believed that he got his best ideas after being on the river and became interested in the “three-day effect”—a term coined by a bookseller in Salt Lake City who noticed that some “magic” seems to happen after three days outside. Dr. Strayer teaches a class called Cognition in the Wild at the University of Utah. Florence joined the class when they went camping for three days in the desert. “It was a helpful way for me to start to frame some of the theories about what’s going on in our brains and then of course to experience some of it too by spending three days outside.” Dr. Strayer has found that people have about a 50% improvement on a cognitive function test after a few days outside. He attributes this to a reduction in activity in the executive function part of the brain while in nature that allows other parts of the brain that are more creative and sensory based to be more active. As Florence says, “We become more keyed into our so-called animal senses. When that’s happening, our thinking brain is kind of reclining a little bit so that when we go back into our executive functioning three days later, we’ve had a rest. It’s like a muscle that we’ve rested and is then fired up and sharp.”

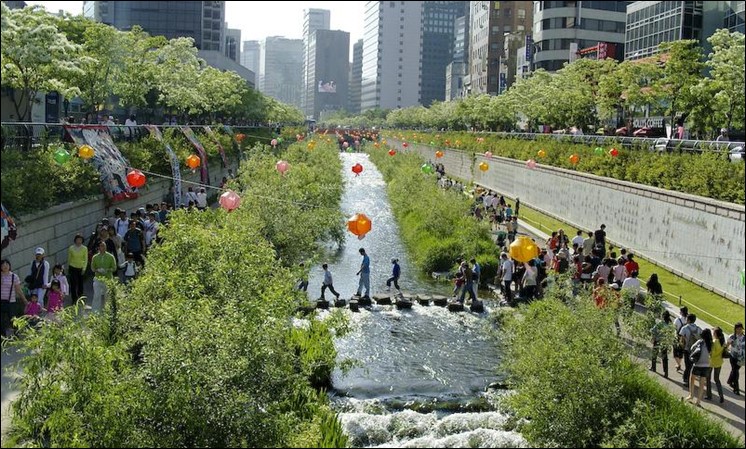

Jeff asked Florence about potential key learnings that could be applied by the EWN Program, our communities, and our listeners. One of the takeaways that Florence notes is the importance of designing spaces, especially in urban areas, where our senses can come alive in a comfortable way. “When we’re in modern life and in our cities, our senses are assaulted in ways that we just accept and don’t really think a lot about. Cities are noisy, they smell bad, and there are flashing lights everywhere.” She recounts a trip to Seoul, South Korea, where she visited the Cheonggyecheon canal that had been redesigned to be a natural space. “They daylighted it and landscaped it. They put trees around this canal. Acoustic engineers came up with little water features and waterfalls and a walking path. The whole thing is about 15 or 20 feet below street level in a very busy downtown neighborhood. When you descend into this kind of lovely trail along the canal, you don’t hear the traffic noise. What you hear is the sound of water and the sound of birds. I thought that was really brilliant—using acoustical engineering to really help reconfigure our landscapes to make them more compatible with our animal sensory nervous system.”

Florence believes that these kinds of urban natural spaces should play a significant role in USACE infrastructure projects. “I think the health piece should not only inform a lot of these projects but actually be a priority for them. In the wake of climate change, a global pandemic, war and strife, and the disunion and incivility that we’re seeing, there’s this concept of urgent biophilia—that having these green spaces accessible and high quality in our urban and suburban areas is absolutely critical for dealing with these stresses that we’re facing.”

In her latest book, Heartbreak: A Personal and Scientific Journey, Florence talks about the restorative effects of nature, particularly after personal trauma. “When we experience awe—and by the way, about 25 percent of the time we experience awe is in the natural world—it really changes our behavior, and it can help rewire our brain in some profound ways. There’s something about feeling that we are small and humble in the universe. That feeling that we all get when we look up at the sky is really good for us psychologically. It makes our own problems seem slightly less significant. It makes us feel more connected to the world around us—and this was kind of a surprise to me—it makes us feel more connected to each other.”

Florence’s call to action is this: “We can construct our lives in a way that helps facilitate our mental health; that should be a priority for all of us and for our children and for our neighborhoods. I really encourage people to get involved with their communities, encourage more trees, more playgrounds, more parks, more recess for kids.” Jeff closes with a note of personal gratitude: “I just want to say that your personal and professional journey is very, very inspiring. I truly believe that there is a lot to what nature can offer us on a variety of different levels, including these health benefits. Our conversation for me today has been just such a pleasure and a privilege. Thank you for sharing your story with us.”