This episode starts with a story. In 1604, 79 members of an expedition from France, including Samuel de Champlain, came to Saint Croix Island off the shores of Maine and New Brunswick to set up a colony in the new land. They called it l’Acadie—Acadia. Over the severe winter of 1604 to 1605, 35 of the settlers died, likely of scurvy. In the spring, members of the Passamaquoddy Tribe befriended the French survivors and brought them food; and, ultimately, their health improved. In the summer of 1605, the survivors moved the Acadia settlement to Port Royal, Nova Scotia, and the rest is history. The Acadians went on to play an integral part in the histories of Canada, the United States, and France. Today, that 6.5-acre uninhabited island and its very significant history is threatened by high tides, shoreline erosion, powerful winter storms, and more—all exacerbated by climate change.

In Season 6, Episode 6, host Sarah Thorne is joined by cohost Jeff King, National Lead of the Engineering With Nature Program, US Army Corps of Engineers, and the USACE Project Lead for collaboration on the Saint Croix Island activities; Donald Soctomah, Tribal Historic Preservation Officer for the Passamaquoddy Nation; Becky Cole-Will, Chief of Resource Management for Acadia and Saint Croix Island National Parks, US National Park Service; and Amy Hunt, Senior Project Manager at EA Engineering, Science, and Technology, Inc. in New Hampshire. They are working together to figure out how to use nature-based solutions to protect and preserve Saint Croix Island and its unique historical significance.

Each of the guests speaks to the unique nature of Saint Croix Island and their personal affinity to it. Donald notes that “Saint Croix has always been a special place, not just for the one winter that the Acadians spent on it but also for the last 15,000 years of Passamaquoddy history. The Island holds a lot of history, and its location is really important because it’s a transition zone going from fresh water down the Skutik-St. Croix River into the ocean. That’s the stopping place. Or if you’re going from the ocean into the fresh water, Saint Croix Island is right in this beautiful area. It is the most beautiful area. That’s why my ancestors settled here.”

The guests also note the Island’s importance as a symbol of the impacts of climate change. As Donald notes, “When I look at Saint Croix, I look at it as a symbol of the change that’s going on related to climate. Because right before your eyes, you can see the rising ocean, the erosion, the shrinking of the Island. Every time I look at that Island, I think about climate change and the importance of trying to make other people aware of it.”

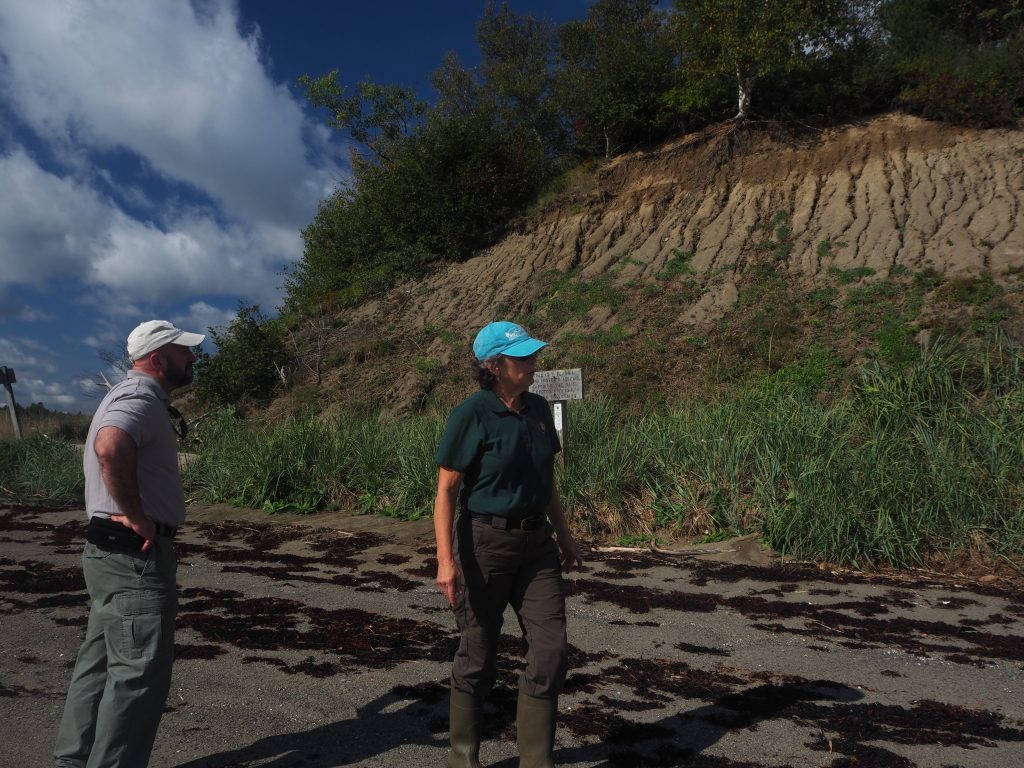

Situated in the middle of the St. Croix River between Maine and New Brunswick, Canada, the Saint Croix Island International Historic Site faces significant erosion threats from a tidal amplitude of about 24 feet and a southern bluff that is highly impacted by weather and climate change. Between 2015 and 2016, the bluff lost about 233 cubic meters of sediment due to a couple of very severe storms that hit the island. As Becky notes, the Park Service has recognized erosion as a problem since the Island became a monument in 1948: “Since that time, there’s been various considerations of how to manage the Island, how to protect it from erosion. Should we try to build some kind of structures to prevent erosion? Should we simply throw up our hands and say, well, it’s going to erode away? Should we do something called perhaps ‘managed retreat’? But the opportunity to work with Jeff and Amy around thinking about what could be a nature-based solution for protecting the island was exciting. It will give us a range of alternatives to consider for long-term management and preservation of the island in partnership with Donald and the Passamaquoddy Tribe, Parks Canada, and other agencies.”

“When you think about a site like this, you can’t really go in with the idea that conventional infrastructure is the right way to do it,” Jeff adds. There are so many things that we want to be considerate of and certainly there’s the traditional ecological knowledge that Donald and the Passamaquoddy Tribe bring to this conversation that we must integrate into the ideas that we put forward. Given the aesthetic of the island, we have to be thinking about nature-based solutions because of the rich heritage that we want to preserve for generations to come.”

Amy talked about the project’s strong, long-term, multidisciplinary, international collaboration, including long-term data collection and monitoring of the island by several parties. “We wanted to collect and use all the existing data available and gain insight from all the folks who had been observing the erosion at Saint Croix and monitoring and documenting it. We’re leveraging their expertise and resources as we work together to conduct research that lets us look at potential options to use natural and nature-based features to stabilize and mitigate the ongoing erosion.” Jeff adds, “This is one of those rare opportunities where we have brought together so many different engineers, hydrodynamic modelers, civil engineers, coastal engineers, landscape architects, and many other scientists who are all very interested and engaged in looking at the island. We’re using all this information and all these skill sets to help us come up with designs for nature-based solutions that we hope will be very effective.”

Donald and the Passamaquoddy Nation will play a critical role in designing the project on the Island, which is a part of their traditional territory: “We’re going to provide our knowledge of the workings of the ocean and the fresh water, our knowledge of the landscape around the Island, and provide history. I’d like to see the project be culturally based, and not disrupt the ecosystem around it, because there’s other factors, the visual factor, the factor of people needing to go to the island. It’s such an important piece of work that’s going to be done.” Donald also notes the long-term implications of this project: “If this is successful, we can start applying this approach to the many islands in the Passamaquoddy Bay and maybe all along the coast of Maine, working with the National Park Service, as they’re in charge of a lot of the coastal islands. They might be able to replicate this.”

In June of 2023, the National Park Service hosted a workshop that brought together about 25 participants—biologists, geologists, engineers, planners, policymakers, and Tribal officers—to discuss the challenge and the opportunity and learn more about the history of the Island. The purpose, as Amy describes it, “was to ask the right questions and cast a really wide net, to gather as much information as possible, then whittle it down to a few specific priorities. I think the process worked pretty well.” Becky adds, “We’re bringing all of these people together. The first day we spent thinking about what could be done. Then people had an opportunity to get out there and see the island and say, ‘I get it now.’ There was a lot of reality checking and ground truthing that was fascinating to hear. So, I think that it was incredibly valuable to have participants think, do some work, then see the island.”

Jeff really appreciated the guests sharing their insights and perspective. He noted that the work is ongoing: “We’re really just getting started. Brian Davis at the University of Virginia has been working collaboratively with the project partners to come up with designs and renderings that we want to discuss with Donald and the Passamaquoddy Tribe to ensure that we’re integrating traditional ecological knowledge along the way. I’m just so excited about where we’re headed and the opportunities this project will offer.”