In this episode, Lieutenant General Scott Spellmon joins Todd Bridges, Senior Research Scientist for Environmental Science and National Lead for the Engineering With Nature (EWN) Program, and host, Sarah Thorne, as their special guest. Lt. Gen. Spellmon is the 55th Chief of Engineers and the Commanding General of the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE). We’re discussing the role of EWN, the importance of innovation, partnerships, and the General’s perspective on priorities for the future.

Lt. Gen. Spellmon opened the conversation by emphasizing the importance of EWN and thanking Todd for his leadership: “It’s important to all of us, not just us within the Army Corps of Engineers but certainly with our many partners, our elected leaders, and, frankly, the American people who live, work, and recreate on the water. They all want to see us succeed as we continue to endeavor to engineer more with nature in everything that we do across our great country. I have committed to this in congressional testimony, and I’ll just say it upfront—we’ve got to do more of this in our projects and in our programs. A personal thank you, Todd, for your great leadership in working to help us advance EWN across the Corps.”

An engineer by training, Lt. Gen. Spellmon graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1986 and was commissioned into the Engineer Battalion. For the first 29 years of his career, he was in the operational Army, serving in many Engineer Tactical Battalions and Brigades. Then, as he notes, late in his career in 2015 he was brought over to USACE to lead the Northwestern Division. Spellmon has been serving as the Chief of Engineers and Commanding General for USACE since September 2020.

According to Spellmon, the Northwestern Division was a great introduction to EWN, because the approaches to addressing the challenges of the two river basins in the division, the Columbia and Missouri rivers, were very different. As he recounts, in the Columbia River Basin, EWN and nature-based solutions were expected by stakeholders and something USACE worked on every day.

In the Missouri River Basin, there was a lot of skepticism: “In 2019, I was out in a field hearing in Iowa following the 2019 bombogenesis that came through and overtopped nearly every levy we had between Omaha and St. Louis. In the field hearing, one of the things I talked about was the need for more setback levees on the lower 735 miles of the Lower Missouri River—a setback levee to me is EWN—giving the river more room to roam. After that hearing, a prominent stakeholder came up to me and said, ‘Spellmon, don’t ever mention those two words—setback levee—again on this basin.’ And I remember telling that stakeholder, ‘Well then you’ve got to be prepared for more of the same.’ That’s a very extreme example of some of the skepticism that’s out there, but that’s what we’re faced with in some corners of our enterprise internally and certainly with some of our partners.”

Spellmon adds, “We need to make the case of the comprehensive benefits that EWN brings to our program. We have so many examples where EWN is going right. This podcast gives us a chance to share, not only internally, but with our many partners, how this can be done and what ‘right’ looks like.”

As the top leader of USACE, Spellmon notes the challenges USACE faces due to increased demand and explosive growth—USACE has gone from being a $20 billion program historically to now over a $90 billion program. “That massive program, that massive workload, is our number one challenge but also our number one opportunity. We really have to be innovative in taking the team that we have today that was structured for that $20 billion program and transforming it into one that can deliver on a $90-plus billion program. And innovation is key, thinking about things differently and executing them differently out in the field. There are so many opportunities with EWN that are going to help us get after this challenge.”

In his travels across the country to engage with USACE teams, Todd says, “I see a lot of excitement and energy across the Corps. We’re leaning into this future of innovating and combining nature and engineering.” He also notes the growing pains associated innovation and change. “There’s really no easy path to innovation and change in an organization with 38,000 team members and a legacy that goes back over 200 years. We should expect and plan for tensions and growing pains. That’s not a symptom of failure. That’s actually a symptom of growth and progress. If you don’t have any tension in your organization, you probably aren’t doing anything important. The Corps of Engineers is a great organization and it’s up to the challenge of being a better, more innovative organization in the future—and yes, EWN is a part of that.”

Spellmon adds that USACE has several success stories: “Some of the things we’ve done in the past were actually ‘engineering with nature.’ We just didn’t call it that when we started down this path.” One example is the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP) in 2000. Its purpose was to improve what USACE had done in the Central and Southern Florida Project of the 1940s that built a system of canals and levees to provide better flood control in south Florida. He notes, “It solved the flooding problem that had endured for many years and enabled agriculture and development in ways that I don’t think people ever contemplated back when the project was first authorized. Our engineers back in the late forties, early fifties, never contemplated the water quality challenges that would emerge in Florida over the ensuing decades.” CERP reexamined the original work and considered potential improvements. Part of that was the Kissimmee River Restoration where the natural bends in the Kissimmee River north of Lake Okeechobee were restored, returning the natural vegetation that was once there. “If you look at that landscape today, the wildlife has come back, and natural vegetation actually serves as a filter for many of the contaminants—the nitrogen and the phosphorous in that water column. It is one great example of EWN, but we didn’t call it that back then.”

A challenge that both have encountered is the perception that EWN is an alternative to traditional engineering approaches. As Spellmon notes, “One of the challenges that we have within the Corps is that too many folks have the mindset that we’re advocating for EWN as a substitute for [traditional] engineering solutions, and that’s not what we’re saying. EWN compliments our engineered solutions. We have to find those cases where we can really get some complimentary effects—multiple benefits to our engineering designs.” Todd adds, “We need to get past the nature or engineering paradigm. It’s a false choice—either this or that. It’s finding the balance and the combination and for us to be more explicit about how nature contributes to the value of our overall system in terms of the benefits to engineering and economics, but also the social resilience that our communities need, as well as the environmental resilience.”

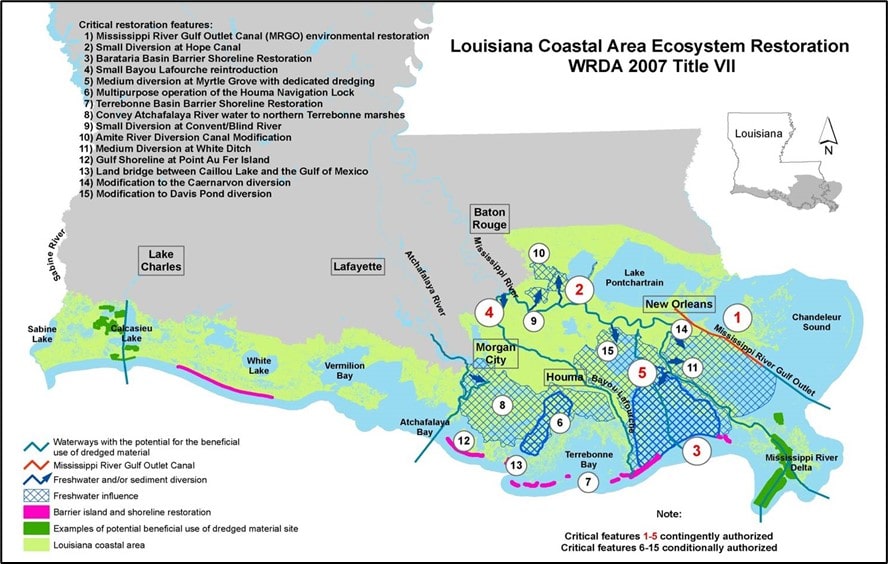

Spellmon notes the effectiveness of the Hurricane and Storm Damage Risk Reduction System in New Orleans, Louisiana, during Hurricane Ida in 2021 as a case in point: “If you look at the way that concrete, steel, and compacted earth performed, it performed as it was designed in protecting the city of New Orleans. But my argument is it performed as it was designed because it had a great set of shock absorbers out in front of it—all the barrier island work that the state of Louisiana has done over the past decade out in the marshes that absorbed a lot from that storm before it even got to the system.”

Spellmon goes on to talk about the leadership and innovation needed to deliver on USACE’s unprecedented $90 billion infrastructure mandate. He talks about three things. First, doing a better job sharing EWN examples and opportunities in his testimony to Congress and in his communications with the 42 USACE district commanders. Second, listening more to our partners and groups like The Nature Conservancy that are on the ground working on projects with USACE. The third is innovating, “listening to new ideas and being open to applying them in the field.”

Todd agrees, noting that he regularly hears from practitioners about how important it is for them to hear leadership within the USACE provide clear direction and intent. And on the importance of listening, he added, “Effective listening requires a good measure of humility. We don’t always have the right answer. We need others to contribute to codeveloping solutions, and that requires an ability to actively listen and to engage substantively and over the long-term with our partners and stakeholders. That’s a work in progress for many government agencies, in my experience. There are great examples of this practice within the Corps that we can expand.” He continues, “Progress runs on the rails of relationships. That’s the experience I’ve accumulated in 30 years. There really is no progress without relationships with others.”

An important component of leadership is setting bold goals. Todd highlights the 70/30 goal for beneficial use of sediment, as an example: “I’d like to commend Lt. Gen. Spellmon’s leadership on the goal he set and put the scope in perspective. USACE dredges about 200 million cubic yards of sediment a year. So going from 30% beneficial use to 70% beneficial use is no small undertaking. An organization as great as the Corps of Engineers needs to have substantive goals—I might even use the