Extreme storms and rising sea levels are putting America’s coastal national parks at high risk. How best to conserve and preserve the unique landscapes and important cultural heritage of these national treasures was the challenge facing our guests. In Season 8, Episode 3, host Sarah Thorne and Amanda Tritinger, Deputy National Lead of the Engineering With Nature (EWN) Program, US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), are joined by Brian Davis, Associate Professor of Landscape Architecture at the University of Virginia (UVA), and Cathy Johnson, Coastal Ecologist, Northeast Region, National Park Service (NPS). Along with their colleagues and collaborators, Brian and Cathy are working with nature and incorporating innovative nature-based solutions (NBS) to combat the significant effects of climate change on three coastal parks.

A guest in Season 2, Episode 2, Brian talked about expanding the practice of EWN through the application of landscape architecture. As a member of the Dredge Research Collaborative, he contributed to the recently published book, Silt Sand Slurry: Dredging, Sediment, and the Worlds We Are Making. Brian is passionate about the opportunity that NBS provides to protect natural resources, while also designing for people—protecting the things we value and the way we use public spaces. “Traditionally a lot of design practices saw those two things as separate—you would do one via conservation and the other via design. One of the amazing things that’s happening through landscape architecture and EWN and NBS is to unify those things. That’s a through line in all my work these days.” He’s brought that passion to UVA where he is teaching the next generation of landscape architects about landscape architectural theory, NBS, and the technical practices and techniques needed for effective coastal design.

Cathy is an ecologist who has been with the NPS for the past 5 years. She’s passionate about the NPS’s dual mandate of conserving natural resources and preserving cultural resources. “I feel so lucky to work here to preserve the natural and cultural resources and values of the NPS for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations.” She adds, “Everything is intertwined in some way—natural and cultural resources, recreational opportunities, infrastructure, interpretive opportunities for visitors. I find myself spending a lot of time working on things outside of my wheelhouse. So, I’m always learning and that’s fun.”

Cathy notes that NPS’s challenging mandate is made all the more difficult by climate change and its broadscale impacts, especially along the coast, and the resulting unpredictability of future conditions: sea level rise causing changes to habitats and species; saltwater intrusion impacting wells and causing loss or degradation of archaeological resources; and increased storm surge and flooding impacting buildings, roads, and other infrastructure are just a few examples. Cathy has been incorporating NBS to help coastal parks adapt. “It’s really exciting to be working on NBS with Brian and his team because NBS can play a role in addressing almost all of those issues.”

About three years ago, Brian and Cathy came together to form the Preserving Coastal Parklands Team. As Brian describes it, “Our focus was on the 88 coastal national park units and to specifically identify a couple within the Northeast Region. The idea was to bring together designers and scientists, as well as engineers and other subject matter experts, that could work with NPS in these different contexts and develop new nature-based solutions to the problems they were facing.” They also wanted to identify solutions that could be adopted by others. “We thought that we might be able to understand things, by working with the NPS, that could be adapted by state, local, and county parks—places that maybe don’t have access to people like Cathy or the resources.” The three projects they ultimately focused on are located at the Colonial National Historical Park, Assateague Island National Seashore, and the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historic Park.

The Colonial National Historical Park in Virginia stretches from Yorktown to Jamestown Island. It is connected by a 23-mile-long parkway and is bounded by the York and James rivers in the Chesapeake watershed. While the emphasis of this park is historical, Colonial also has abundant and diverse natural resources, such as extensive marshes and breeding bald eagles.

Assateague Island National Seashore was established in 1965. It’s a 37-mile-long island along the coasts of Maryland and Virginia. Most of the Maryland district is managed by the National Park Service as Assateague Island National Seashore. The State of Maryland manages two miles of the Maryland district as Assateague State Park. The Virginia district is managed primarily by the US Fish and Wildlife Service as Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge. The mission of the National Seashore is to preserve and protect the unique coastal resources and natural ecosystem conditions and processes there and to provide high-quality, resource-based recreational opportunities. Natural resources are front and center in the park’s mission.

The Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historic Park on the eastern shore of Maryland is the third park Cathy and Brian’s teams are working on. Congress created the park in 2014 to preserve and interpret the historical, cultural, and natural resources associated with the life, work, and legacy of Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad. The park landscape is intertwined with the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge and the Maryland State Park. Both of these legislative partners are engaged in the management at the park and the visitor center is comanaged with the State. As Cathy and Brian discuss, they are working closely with relevant parties to better understand how to protect the cultural significance of the park, as well as the landscape.

Cathy notes the unique value of NBS to the National Parks. “What the Park Service and other land managers have often used in the past are primarily hard structures. You can meet some of your goals that way, putting up a wall to protect a specific area or a jetty to minimize sediment input to an inlet, but you’re impacting the landscape adjacent to that area in a negative way. So, how can we get the benefits—the protection from some sort of hybrid or natural infrastructure—while not having the same adverse impacts to the adjacent landscape? NBS seems to lend itself to that a lot. Working with Brian and his team at UVA has just been an amazing collaboration for me. He and his team, along with his landscape architect colleagues, are the creative minds behind the innovative NBS options we’ve been developing.”

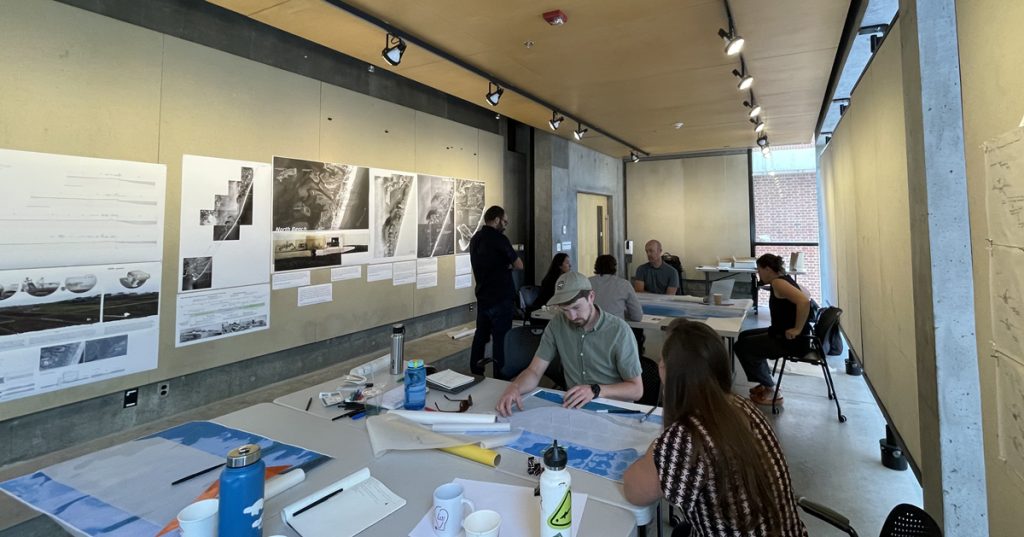

Asked what they have learned from their experience on these projects, both Brian and Cathy note the value of collaboration. “One of the key lessons that we took away from Assateague,” Brian says, “was the value of being able to work with and listen to the people that are managing the landscape—especially the Park staff, but also other special interest groups, people that go out there for particular reasons or have some stake in the future of the place and some ideas about it. That’s an insight that we’ve tried to bring to the other projects that we’re working on.” Cathy agrees, noting, “Colonial was our first project, and we were learning how best to work with the Park staff. At Assateague, we had strong engagement by all the staff—people from diverse programs: facilities, maintenance, cultural, interpretive, and leadership as well as the natural resource staff. Everybody was really excited and engaged and wanted to jump into this new NBS concept. They were all about the creativity.”

Amanda reflects on how others can use these examples of NBS applications in these projects: “What you and your team are building is a framework for how to approach these issues with nature-based solutions, to achieve the balance of these multiple needs and multiple benefits. You are creating a framework that ideally could be picked up by others in similar situations.” She asks, “How do you ensure that this innovative approach that you’ve developed to these very different complex solutions can be applied in different contexts while still addressing those larger challenges?”

Brian responds: “It requires additional coordination. It requires a time and scope built in for listening, not only studying the landscape itself but identifying individuals and groups, representatives that can teach us those things. And I think, honestly, the support of the EWN program and the interest of the NPS has made that unorthodox and complex approach possible.” Cathy agrees noting the value of the projects they’ve worked on as examples of what is possible, along with supportive policies: “From the federal government, there’s a lot of encouragement for NBS and in the past 5–10 years, a lot of documents have come out, guidance and examples for land managers to use to implement NBS. These and other policy memorandums, manuals, and such are super important because they are telling us that we are to incorporate principles of NBS into our policies, our plans, our guidance documents, agreements, and other instruments for management and costewardship.”

When asked for their calls to action to listeners, Cathy encouraged people to “go out and visit your parks and the other natural places around you to better understand what’s at risk from climate change and talk to other folks about it. Make sure your children and other young people that you interact with learn about climate change and what we can all do to help keep these resources around for the future.” Brian’s call to action is one of optimism: “Don’t give in to pessimism. Sometimes, especially studying climate change or sea level rise, or even working on NBS, the scale of the problem can seem daunting. But just being out in these landscapes—meeting the people that work in them and visit them—leads to ideas about preserving those values and understanding better what’s possible in the future. That fills me with optimism.”