Since 1970, the bird population in North America has declined by about 3 billion birds. In Season 8, Episode 5, host Sarah Thorne and Jeff King, National Lead of the Engineering With Nature (EWN) Program, US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), are joined by our special guest, Dr. Elizabeth Gray, CEO of the National Audubon Society. Elizabeth is an ornithologist and a world-renowned champion of science-based conservation and leads an organization dedicated to protecting birds by altering the course of biodiversity loss.

Elizabeth is the first woman CEO of Audubon since its founding in 1905. As she describes it, her career has been defined by often being the only woman in the room: “I’m a scientist and I think, like a lot of other STEM fields, the field’s been historically male dominated.” She adds, “It’s really such a profound honor to serve as Audubon’s first woman CEO. I take that not just as an honor, but as a huge responsibility, a responsibility to the mission—to protect the places birds need—but also a responsibility to serve as a role model for other women and men who want to be leaders in conservation and the environmental space.”

Elizabeth’s life has been defined by her sense of curiosity, and animal behavior in particular captured her attention. She did her undergraduate thesis on homing pigeon navigation, then went to grad school to further study bird behavior. “In my first field season, I was comparing the behavior of Red-Winged and Yellow-Headed Blackbirds on a marsh. The first field season was great. The birds showed up and I collected a lot of data. In my second field season, the Yellow-Headed Blackbirds didn’t come back. So, I had to change the whole structure of my thesis. But more importantly, I didn’t understand what happened to these Yellow-Headed Blackbirds. So, I just started to ask myself, ‘What’s going on with the planet? What’s going on with the environment? There must be something that needs investigating here.’ And that really became my impetus for becoming a conservationist and environmentalist.”

After grad school, Elizabeth spent several years in Hawaii studying endangered Hawaiian Honeycreepers, birds that live on the slope of the Mauna Kea volcano. Warming temperatures have caused mosquitoes—which can spread avian malaria—to move up the slope of the volcano and increased mortality of the endangered Honeycreepers. Putting this all into context, Elizabeth says, “Birds brought me to science; then they brought me to conservation; then, ultimately, they introduced me to this concept of climate change. They’re indicators of the health of the planet. They’re beautiful, fascinating, magical creatures in and of themselves. And when I came to Audubon, it just felt like I was coming full circle to the creature that kind of has guided me throughout my whole career.”

In her lifetime, Elizabeth has seen significant changes in bird populations. “Bird populations are down by over 3 billion birds just in North America alone. This is just really tragic, and we know two-thirds of those birds are threatened by climate change. When I go out in the field, I see increasing habitat loss and habitat fragmentation. Climate change is a magnifier of all these effects, and birds are indicators of planetary health—really the sentinels and the symbols of how the planet’s doing.”

Elizabeth says Audubon’s goal is to “bend the bird curve”—to halt, and ultimately reverse, this decline of birds across the Americas. “We’re going to do this by using science; by building strong partnerships; and by finding solutions that are positive for birds, for people, and for the planet because we believe that what birds need—clean water, clean air, a healthy food system, a healthy climate—is also what people need.”

Audubon’s 5-year strategic plan, called “Flight Plan,” is designed to make “bending the bird curve” actionable. The Flight Plan is focused on four areas: habitat Conservation, climate action, policy, and community building.

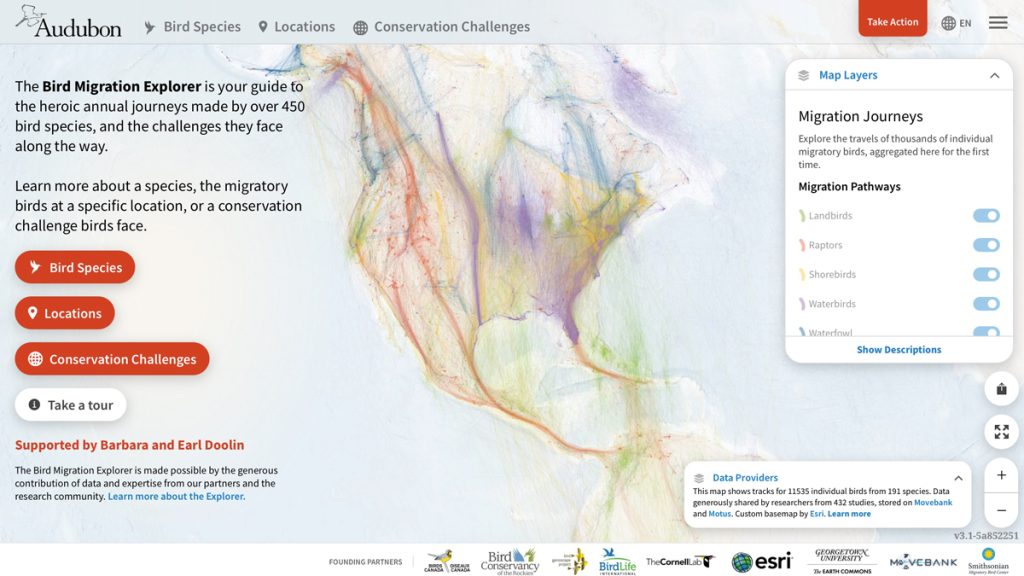

One of the foundational elements of the strategic plan is to “follow the birds” using new technology and science to track birds across the Western Hemisphere. Audubon’s Migratory Bird Explorer is a publicly available platform developed with several partner organizations to track and allow people to explore bird migration. As Elizabeth says, “Anybody can go to this platform and see what birds are in their area and track birds across the hemisphere.”

Elizabeth notes how these efforts continue a tradition going back to the early 1900s when Audubon began protecting one of the last Reddish Egret rookeries. At that time, the fashion of women wearing hats with feather plumes caused a lot of the plumed birds to become threatened and endangered. “So, we really struck out over a century ago to turn that around. And the effort to protect these plumed birds grew into Audubon’s Coastal Bird Stewardship program.” She adds, “With the Coastal Bird Stewardship Program now, we have over 500 sites in coastal areas. We have about 1500 volunteers who are working with us, with 250 partner organizations. We’re working to protect habitat for nesting birds like Piping Plovers, Western Snowy Plovers, Least Terns, Black Skimmers, etc. But it’s not just about protecting bird habitat for birds. These coastal areas are also important in terms of cobenefits for coastal communities.”

Top Pick for Practitioners

Ever heard of Thin Layer Placement, or TLP? It’s a breakthrough for wetland restoration! Instead of disposing of dredged sediment from navigation channels, TLP spreads a thin layer over wetlands degraded by erosion or rising seas. This boosts elevation of the wetlands and restores habitat, including nesting grounds for birds. The “Thin Layer Placement Guidelines” from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers provide practical steps, case studies, and best practices to help practitioners create resilient wetlands, reduce flood risks, keep channels open—and of course, help the birds. Learn more about TLP at EngineeringWithNature.org, and listen to our feature show on TLP in Season 6, Episode 9 of the EWN Podcast.

Collaboration and partnerships are key to addressing these complex and interconnected issues, according to Elizabeth. “I think Audubon is well known for bringing together unlikely partners, industry, local communities, policy makers, decision-makers, government officials, Indigenous communities, and other conservation organizations. We often have different priorities, but we’ve found that you can get people who have different priorities, even different values, certainly different approaches, to sit at a table if you can align around the outcome that you want to achieve together.” She adds that birds are Audubon’s “superpower.” “Birds don’t pay attention to geographic boundaries. They don’t pay attention to what divides people or countries and things like that. They’re really the ultimate unifier here. And I think to me, birds remind us of our shared humanity and the fact that we really share this planet.”

Elizabeth describes some of the types of collaboration and innovation underway. In the Gulf of Mexico, Audubon is working with developers and federal agencies to assess the risks of development of offshore wind generation, to both promote renewable energy and protect migratory bird populations. In the Western US, Audubon is working with private property owners in a program called “Audubon Conservation Ranching” that promotes sustainable ranching practices that in turn increases bird habitat, increases carbon storage in grasslands, and helps ranchers get more profit from cattle grazing. “By working with Audubon and putting together these really robust management plans for how they manage the lands and how they graze the lands, property owners get Audubon Certified bird friendly land designations.”

Nature-based solutions (NBS) play a key role in Audubon’s efforts. As Elizabeth notes, NBS can contribute significant greenhouse gas reductions through protecting, restoring, and appropriately managing natural areas, coastal systems, mangroves, grasslands, and forests while also delivering cobenefits to nature and society. “The real beauty of NBS are the cobenefits we’ve been talking about. Protecting bird habitat helps us fight climate change because you are sequestering and storing carbon, you are protecting water sources, and you are increasing resilience to extreme storms and weather events.”

Jeff notes the strong synergy and alignment between the mission of Audubon and the objectives of EWN. “This really strikes a nerve with me in terms of how these kinds of expertise and skill sets create opportunities. With nature-based solutions, we can create resilience while also enhancing habitat and biodiversity and accomplish many more cobenefits. I see so many things that are complementary here, and I’m just excited about what you’re doing and seeing on the horizon within Audubon.”

Elizabeth’s call to action speaks to everyone: “If you’re in government, support climate policies, regardless of how you vote. If you work in academia, we need you to invest in climate research and technology. If you work in science, please doggedly pursue practical solutions for a net-zero future. If you’re in business or if you’re in industry, commit to sustainability, commit to responsible supply change management. If you have time and you have passion, make sure you vote, organize, and volunteer for groups that support conservation and the work that we’ve been talking about on this podcast. And certainly, if you have wealth, we would love for you to donate to organizations like Audubon. We’re working across all sectors. We’re really dedicated to making this planet a better place through the power of birds. And then finally, even if you only have $20, you can become a member of the National Audubon Society.”

Jeff commended Elizabeth for the wonderful insight into what Audubon is doing today and noted that he looks forward to future collaborations and conversations.