Nature is a powerful thing. While hiking in the White Mountains of New Hampshire in 2006, our guest let go of her dream to compete at the 2008 Olympics to pursue a career protecting the environment. In Season 8, Episode 6, host Sarah Thorne and Jeff King, National Lead of the Engineering With Nature (EWN) Program, US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), are joined by our special guest Robyn DeYoung, who now leads the US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) Green Infrastructure Program. Through the Green Infrastructure Federal Collaborative, Robyn is bringing federal agencies together to advance nature-based solutions (NBS), including finding ways to streamline permitting and helping communities navigate funding. The Collaborative has just released a best practice guide on Federal Permitting and Environmental Reviews for Nature-Based Solutions and short videos for funding and technical assistance.

Nature has always been a big influence on Robyn’s life. “Growing up, I was always playing in the creek in our backyard. We had a neighborhood group that would bike around outside. I would climb trees, jump off into the streams from the rope swings, and that gave me a deep respect and a connection to the land.” The other big influence was field hockey. At Boston University, she found a place that satisfied both of these interests, studying environmental science and playing Division I field hockey. After college, she continued playing field hockey, and the team missed qualifying by one place for the 2004 Olympics. Then while in grad school in 2006, she took that fateful hike that changed her life: “I was at a crossroads, so I went hiking in the White Mountains in New Hampshire and I asked myself, ‘what do I want my future to be like in 10 years?’ And I had this aha moment of ‘I need to let go of the 2008 Olympics and go for my environmental career. Do something that’s bigger than myself,’ so that’s what I decided to do.”

Robyn took a job at the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency and built the first voluntary credit trading program. Despite some initial resistance from industry, eventually people started to come around: “Two years later, one of the people who was the most resistant gave me a call and said, ‘you know what Robyn, I actually do see a benefit in this environmental regulation for business innovation.’ That was my first lesson realizing that you can align environmental regulation with economic prosperity—very helpful for me to see early in my career.”

Robyn joined the USEPA in 2010 working with states and local governments on clean energy, applying all that she had learned—including the value of teamwork that she learned from field hockey. In her current role as Green Infrastructure program manager, she continues to help people work together: “How can we collaborate and use people’s unique talents—even people that might not agree with you, but have great ideas? Because that collaboration and partnership is so powerful, in being innovative and finding the solutions that we need to keep our world a healthy and safe place.”

Green infrastructure can mean different things to different people. As Robyn describes it, “If I’m in a room full of engineers, then green infrastructure means you’re using natural systems—native plants, soils, permeable surfaces—to help with bringing us back to predevelopment hydrology. But for the rest of us, the way that I define green infrastructure is that we’re creating functional green space and other designs so that we can prevent flooding, keep our cities cool, and keep our waters clean using natural processes, using things like rain gardens or street trees.”

Robyn notes that one of the primary functions of EPA’s Green Infrastructure Program is outreach, providing resources to help people understand the economic, environmental and social benefits of green infrastructure. “If you’re a stormwater manager and you want to build a bioretention system, we have a Bioretention Design Handbook for that. If you’re looking to build green streets so that they’re more walkable and there’s more shade when you’re waiting for the bus, we have a Green Streets Handbook. We have free peer exchange webinars. We have models and tools. One of the focuses of our program is to make sure that we have free information so people can design, build, maintain, and monitor the green infrastructure in their cities and communities.”

Robyn explains that stormwater is the fastest growing source of water pollution in the United States: “Whenever it rains a lot—and rain is getting more frequent and flashier—the rain comes down and it hits pavement and picks up oil and trash and dirt and all of that, and it goes straight into our sewer systems that flows directly into our waterways. And if you don’t have nature-based solutions to capture and absorb it into the ground, or to even treat it, then we are polluting our waterways whenever it rains.”

Jeff notes how important it is to offer information and support to communities about how green infrastructure can mitigate stormwater and remove those contaminants. “It’s going to take all of us to achieve the desired outcomes of cleaner waters. And green infrastructure is going to play a huge role going forward.” Robyn agrees, noting, “Once people understand the value of nature in their water infrastructure, I think they really want to do something about it.” She adds that the EPA has funding in its Clean Water State Revolving Fund to support these nature-based solutions to move green infrastructure forward.

Another area where green infrastructure can have a positive impact is in addressing extreme heat. Robyn notes that the number of heatwaves per year has doubled since the 1970s and that 2023 was the hottest year on record. She adds, “The biggest way to reduce heat deaths and our vulnerability to heat is to have more shade trees in areas where historically may have not had that investment in those nature-based solutions. You can see a difference of between 3 and 10 degrees Fahrenheit in urban areas when there are no trees versus where there are trees. So that’s pretty amazing.”

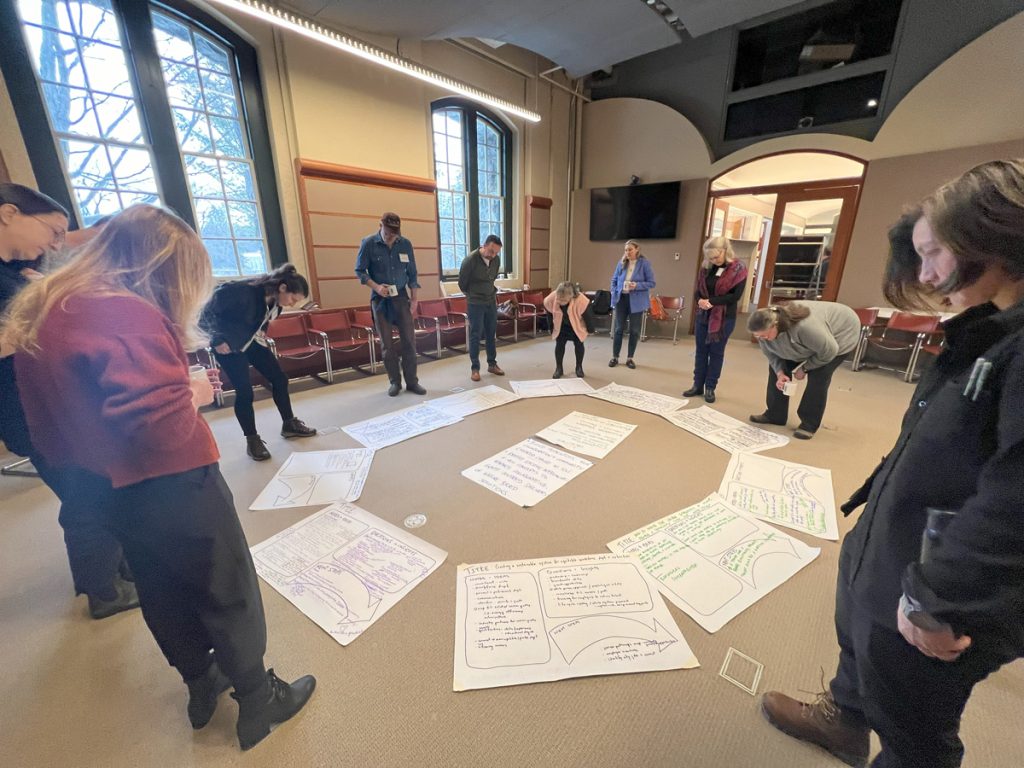

Working with communities and students to support green infrastructure is one of Robyn’s favorite parts of her job. Over the past 15 years, Robyn and her colleagues at EPA have partnered with over 90 communities, providing designs and support. “We have a landscape architect on board, and we work with consultants. And it’s been so exciting to be able to give these communities free technical assistance so that they can plan and design and envision what they want their communities to look like.” EPA also has a college student program called the Campus RainWorks Challenge to encourage students to think about how they could design a more sustainable campus.

Looking forward, Robyn notes some of the focus and priorities she sees in the next year, starting with EPA’s 2035 Green Infrastructure Strategic Agenda that her program has been working on. “I’m a big believer in prioritizing because if we try to do too many things then we do them all very poorly. But if we prioritize and try to do a few things well, then it works out.” She describes three priority areas: (1) Demonstrating the benefits of green infrastructure in ways that align with the economic, environmental, and social benefits that people value. (2) Connecting more communities to federal funding and technical assistance. And (3) continuing to engage with communities. “We want to do everything we can to bring nature-based solutions into those neighborhoods in a way that they want to use them, that’s culturally relevant, so that they can really take it and run with it.”

Robyn’s call to action is for listeners to learn more about what the Green Infrastructure Program is doing and find out about the resources that are available to support individuals and communities interested in green infrastructure. “We have so many different, great resources out there, depending on what you’re interested in. We just redesigned our entire Green Infrastructure website, and we also have a GreenStream listserv where we put out new information that’s going to be coming out, funding, webinars, resources, all that kind of great stuff. If you sign up for our GreenStream listserv (join-greenstream@lists.epa.gov), then you’ll learn about it right away.”

Jeff thanked Robyn for sharing her story the great work that she’s doing. “Well, you’ve got a vision far out to the horizon. All of these different actions and activities that you’ve described are going to really move the needle. There are so many facets to what you do. I’m just thrilled that we could share your story and your journey with our listeners. I think that there’s a lot more, at some point, that we should probably come back and talk about, in particular, future collaborations between your program and mine.”