Bounded by two mountain ranges, the 450-mile-long Central Valley dominates the middle of California and covers about 11% of the State. The Central Valley is divided into two parts: the northern Sacramento Valley and the southern San Joaquin Valley. Technically, because it averages less than 10 inches of rain a year, the San Joaquin Valley is a desert. And thanks to what is called the “great water experiment” of the last 100 years, it is the most productive agricultural region in the world, with more than 250 crops under cultivation. But the current system and approaches are unsustainable.

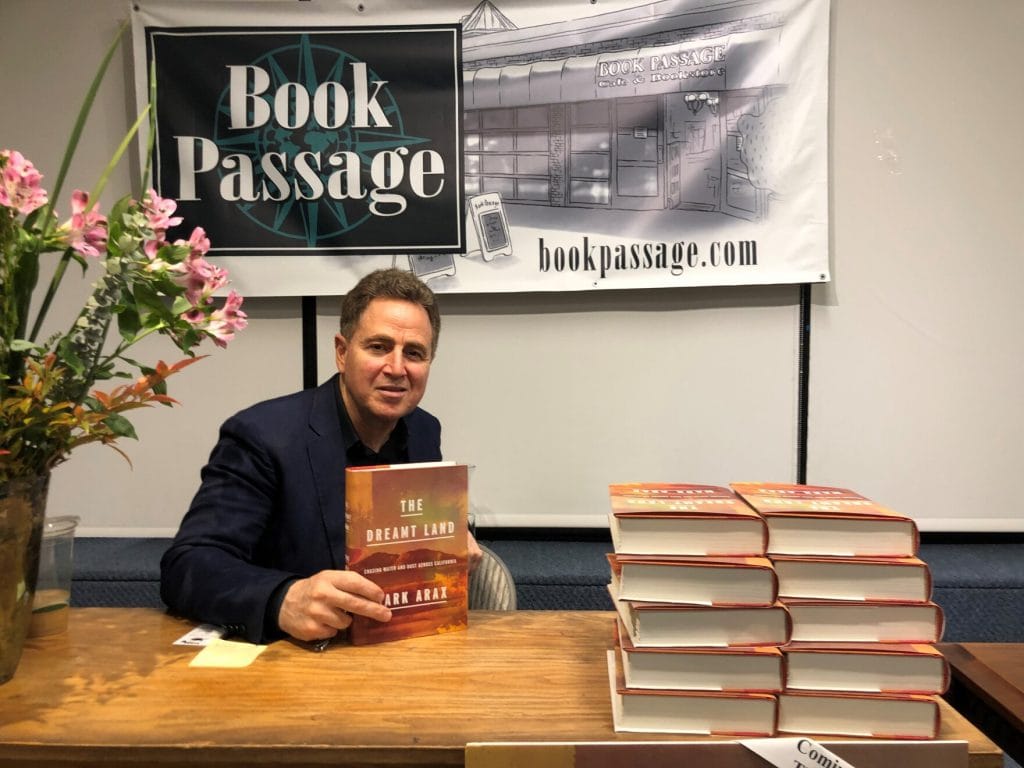

In this episode, host Sarah Thorne and Todd Bridges, Senior Research Scientist for Environmental Science with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the National Lead of the Engineering With Nature® Program, are joined by author Mark Arax. Mark’s recent book, The Dreamt Land, describes in very personal terms the history of California’s water challenges, its unprecedented irrigation experiment, and the emerging threats of climate change.

Both Mark and Todd grew up in the San Joaquin Valley and were shaped by their early experiences, including the irrigation canals that sliced through their communities. As Mark notes, “It never occurred to me back then to ask, why are there irrigation canals? Where is that water coming from? Where is it going to? Who is it going to? This was the story of the reinvention of California.” Water became the central metaphor of The Dreamt Land. For Todd, “the frogs, minnows, and water striders of an irrigation canal were my introduction to aquatic ecology, which has everything to do with my career in life. It was only moving away and looking at it from another place and reading about it that I come to have a deeper understanding of what the Valley was in the past, what it is today, and some of the tensions that exist.”

According to Mark, the Central Valley is “the strangest desert it can be” because of the lack of rainfall from April to October. But in the past, before people intervened, it also featured a number of significant rivers running through it; interior lakes; and in heavy snow and rain years, one of the “greatest wetlands in the world.” Those who came to California to farm this fertile ground believed those rivers had to be “conquered.” In the 1920s, Tulare Lake, which would have covered more than 800 square miles in wet years, was drained using levees and pumps—extraordinary engineering that transformed the land into the richest cotton plantation in America.

Mark has spent 30 years trying to understand the history and continuous transformation of California and the Central Valley. The Dreamt Land tells the stories of the farmers, prospectors, and miners who were drawn to California’s bounty. “The gold rush is not something of the past,” Mark says. “We had to stop the gold rush experiment because it was fouling all the rivers. But then we started the experiment of water extraction and soil extraction. That gold rush mentality has never left California.”

Todd recently toured the Central Valley by helicopter with leadership from the Corps of Engineers and colleagues from the California Department of Water Resources and saw the Valley from a new perspective. Todd’s travel log, The California Swing, tells the story. He notes that the result of “mining” water through human intervention and engineering has transformed the Central Valley into a vast agricultural landscape. “California is the number one agricultural state in the country with $50 billion a year in farm-level sales. Of that $50 billion, more than $34 billion comes from the eight counties in the San Joaquin Valley. Fresno County, where Mark and I are both from, is the number one agricultural county in the U.S.—all of this made possible by water engineering.”

One of the challenges in the West is the vast swings between droughts and floods. “All of those water-moving systems in the Central Valley were designed to even out the differences, to somehow soften that swing from drought to flood,” Mark says. “It was magical. We defied gravity with that system, moving water from one end of the state where it rained to the other end of the state where there wasn’t enough water. And we did a pretty good job. But when you look at climate change now hitching on to the inherent wild swings in weather, all bets are off. This is what we’re confronting today.”

Todd agrees, adding, “With that artificiality comes consequence, in terms of poor air quality, water quality problems, and social inequity. Almost 25% of the population of the San Joaquin Valley lives below the poverty level, alongside very significant profit and wealth being generated within and across agriculture. From the philosophical point of view, imposing artificial landscapes upon a system brings forward these kinds of tensions and problems.”

The vast pumping of groundwater has expanded agriculture well beyond what is sustainable. In the southern part of the San Joaquin Valley, portions of the land subsided as much as 30 feet. The 444-mile-long California Aqueduct is sinking and losing the gravity flow it depends on to move water from north to south. According to Mark: “In the San Joaquin Valley, we have 6 million acres of farmland. To get sustainable, we’re probably going to have to lose a million and a half of those acres. That’s an extraordinary transformation backward to making this land natural.”

Todd closes the episode by acknowledging the importance of agriculture while highlighting the need for balance: “We don’t have modern civilization without farmers and farms. Agriculture is so important to humanity, to California, and to the San Joaquin Valley. The question is balance. Understanding history is vitally important in understanding how to rebalance. How to get to a more stable equilibrium, within science—a rebalance of the system, the social and the ecological.”

In Episode 9, Todd and Mark return to continue the discussion of potential solutions informed by Engineering With Nature approaches.