Imagine restoring a 51-mile-long concrete river—running through the heart of the Los Angeles Basin in California—into a vibrant corridor reconnecting fractured communities and ecosystems. In Season 7, Episode 7, host Sarah Thorne and cohost Amanda Tritinger from the US Army Corps of Engineers talk with landscape architects Alex Robinson from University of Southern California (USC) and Leslie Dinkin from the Kounkuey Design Initiative in Los Angeles. They discuss the use of storytelling, augmented reality, and physical modeling tools to engage people along the river in cocreating a new future for themselves and for the river.

Alex’s work is rooted in his personal experiences with the City of Los Angeles (LA) and its infrastructure, including the LA River, and finding out how people spend their days interacting with these interesting landscapes as they shape their lives and create art. “My work is split between these two parts,” Alex says. “I’m really interested in identifying these places as incredible landscapes while also thinking about how we actually design these things effectively, in a way that brings together all of the assets that society has and really works hard on all levels to fulfill the potential that they have as a landscape, as a place, in the city.”

Leslie recently graduated with dual master’s degrees in landscape architecture and heritage conservation from USC, studying under Alex and working with him at the Los Angeles River Integrated Design Lab (LA-RIDL). Leslie grew up in LA but went to college in Colorado and worked as an outdoor educator for several years in the Rocky Mountains. As she explains, “I would take students up 14,000-foot mountains where we’d swim in Alpine lakes. But the longer I spent in these places, the more I felt I was teaching students that connection to nature only happens when you are way out there, when you can’t see any people or buildings; but this is not where most people live. That prompted me to return home to LA to pursue a master’s degree in landscape architecture and urbanism.” She adds, “After a year in that program, I started a second degree in heritage conservation and realized pretty quickly that I couldn’t design anything new if I didn’t learn about everything that was there before. And so extensive research, storytelling, and listening to community stories quickly became a part of my practice.”

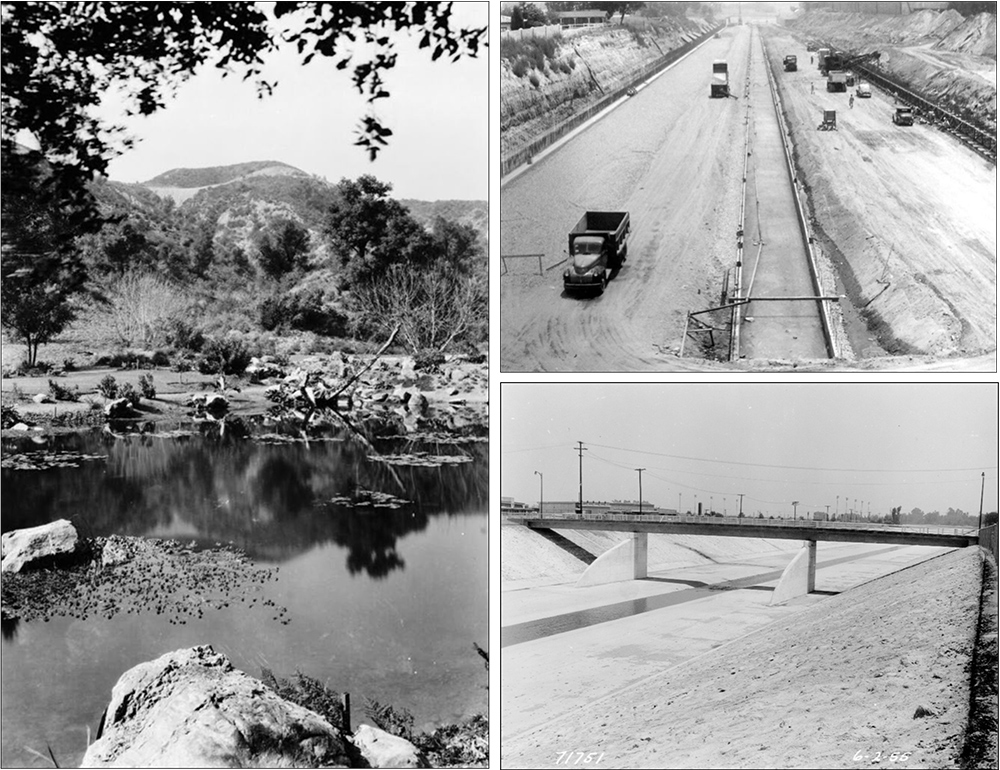

Leslie’s master’s thesis is on the long, sometimes sad, and disturbing history of the LA River, originally known to the Gabrieleño-Tongva Tribe as the Paayme Paxaayt, or the “West River.” It was a transient body of water that brought rich soils to the LA Basin and was described as a lush, life-giving oasis. As settlers developed the region, however, the river was increasingly seen as a flooding threat. In response to the flood risk, between 1938 and 1960, USACE enacted a monumental project to encase the entire river in concrete to protect the surrounding urban sprawl. As Leslie notes, “This massive undertaking severed the river’s connection to its groundwater and essentially erased its identity as a living waterway.”

Fresh out of graduate school in 2005, Alex worked on the Los Angeles River Revitalization Master Plan, one of the first of many plans for the river that tried to bring different values into the thinking about how to transform the river into something more than just an instrument of flood control. “That was a really formative experience for me. I wandered along the whole river, mapping it out, spending time with different communities. I was fascinated with trying to find a way in which we could really begin to make and catalyze change.” He has continued this focus with the realization that, “as a practitioner, I was seeing that we didn’t really have a good collective understanding of where we were or where we could go. We were constrained by a lot of major issues and so many voices and different constituents. They were speaking different languages, all in their own silos, with different visions, not understanding what was really possible. I thought, what if we could bring together all these voices and create a platform where we had a more collective understanding, where people could begin to speak the same language and were able to cocreate something.”

This led Alex to bringing together imaginative artists, working with engineers, to create physical models of the LA River along with advanced visualizations to help people better understand the challenges as context for future opportunities. “One of the things that people don’t understand is the critical flood protection the river provides. It’s really hard to make changes if you don’t work carefully, in a closed feedback loop, with that parameter of flood protection. We had a disconnect where people were just imagining all sorts of amazing, incredible things, but they didn’t understand the hydrology. They didn’t have the tools.”

Alex reached out to the USACE Engineer Research and Development Center (ERDC), which has hydrology modeling in its toolset. As Amanda notes, “You can see how this just clearly aligns with Engineering with Nature. What some people might see as a complex problem, Alex and his team identified as a beautiful, community-based solution. At ERDC, we have numerical and physical models, but how do we get our models to talk to people? I think Leslie and Alex have done a really great job in not only creating that connection but making it meaningful.”

The product of this collaboration with Duncan Bryant, Research Hydraulic Engineer, and his colleagues at ERDC’s Coastal Hydraulics Laboratory (CHL), was the development of a physical model of a section of the LA River with adjacent land owned by the city where there is an opportunity for big changes, potentially including the building of an island that would radically transform the river and change the floodplain. As Alex explains, “This is the crown-jewel opportunity for changing the LA River.” To take the engagement with the model to the next level and produce something that invites people to participate in the process, Alex and his colleagues developed an augmented reality component to visually overlay information on top of the physical model. “This is all the masterwork of my colleague Andreas Kratky in the School of Cinematic Arts and his students. It lets people interact—they can draw on the model in three dimensions using this tool, and they can make comments, and those comments will persist. So, you have this incredible opportunity where a community member can come in and make a comment, draw something, and that becomes input an engineer and a landscape architect can consider in their design process.”

Leslie adds, when they were building the model, “we wanted to make sure that it would be highly tactile, interactive, and user friendly. Making sure it was fun was also really important. We considered the qualities of a model railroad and the joy of selecting and positioning different objects and altering the train tracks. In positioning the vegetation in different places in this model, you can alter the flow of water. The lab created over 2,000 individual silicone pieces that are all magnetic, and they adhere to the model with magnetic paint.” Alex also notes that a camera system captures the modifications that people make, so they can then be modeled to determine the impact on the river system.

This project is unique. As Alex explains, “I’ve never opened the doors as wide as this project in terms of all the different voices and really powerful AR and VR tools—including the water, which itself is a powerful voice. We are opening the door to the hydraulics in a way that I don’t know what’s going to happen exactly. I don’t know what the answers are. And we’re also opening the door to the voices of the community.” He adds, “We just had an event with one of our arts partners, Clockshop. They brought a whole group of people that were from all different backgrounds. They interacted with the model, and we had a different kind of conversation about what does the water want. It was a journey and an adventure for me to get into this space with all these different people.”

A really interesting component of Leslie’s work on the river was the 51 Mile Project. Leslie and a team of students, including a photographer and a documentarian, walked along the entire 51 miles of the LA River over six days in August 2023. According to Leslie, “It was amazing. We each walked with our own inquiry in mind. One of us was focused on ecology and mapping and another on urbanism and access. I was thinking about heritage conservation and narrative ethnography. We documented the river from the headwaters in Canoga Park to the estuary in Long Beach.” Leslie and her colleagues are working on a 90-minute movie documenting their journey and the people they interacted with along the way.

Thinking about how advanced visualization tools support community engagement, Alex says, “I think the model and all the different tools we’ve developed have created this incredible common ground for people to have a conversation and have their ideas and values represented in the system. These advanced tools allow for a much deeper and richer understanding of everything that’s happening. They relieve each person from having to understand and explain everything they care about in terms of the river; instead, they put it on the map. People say, ‘I feel a little bit represented and I can trust that this tool is going to tell the story.’”

Leslie adds, “I think there’s so much to learn and everyone is really coming to the table with different ideas of what they want to see. You have the engineer who wants to save lives. You have the ecologist who wants to see steelhead trout back in the river. How do you balance both of those priorities without really minimizing either person’s worries or hopes and dreams. The model is beautiful because it encourages all sorts of different people to be in one space. What you can learn from one another when you actually listen is probably the biggest thing I’ve taken away from this project.”

Amanda truly appreciates the work that Alex and Leslie are doing: “If I could just represent all of engineers for a minute, I’d like to say, thank you. Thank you for helping us communicate. We try, but sometimes the numbers don’t do it. We appreciate the efforts that you bring to this practice.” She adds, “The last time I was on the podcast, we talked about engineering with empathy. I think the key to empathy is listening and hearing different points of view and giving people a platform to speak and share. Today we’ve heard great examples of what giving those platforms to people looks like and how we can listen better.”

Referenced Colleagues / Organizations

- Duncan Bryant, PhD, PE – USACE CHL – LinkedIn

- Duncan Bryant at EWN

- Jeremy Sharp – USACE CHL – LinkedIn

- Gaurav Savant, PhD –USACE ERDC CHL

- Andreas Kratky – USC Cinematic Arts

- Nina Weithorn, MLA at USC

- Hannah Michael Flynn, MLA at USC

- Mitul Luhar at USC

- Clockshop Los Angeles

- Clockshop: Take Me to Your River: A cultural Atlas of the LA River

- City of Los Angeles Bureau of Engineering

- Friends of the LA River

- Rio Asch Phoenix

- Camille Shooshani