Highlights from the Canada Nature-Based Workshop, June 2022

By Paula E. Whitfield, NOAA retired

Setting the Stage: The Problem and the Solution

What mental image do you conjure when you think of “cold regions”? Perhaps because I grew up in Washington State on a bluff overlooking Puget Sound and now live on Maine’s “Bold Coast,” I picture frothy waves crashing against jagged, five-story cliffs that loom over a cobble, log-strewn beach. You might think of a snowy expanse of desolate tundra or a conveyer belt of cracked and calving glaciers. All would qualify, at least according to the generous definition provided by Hayley Shen1 who describes cold regions as including both polar and nonpolar regions and as “part of the earth system characterized by the presence of snow and ice at least part of the year.” However you define it, risks from coastal hazards, like erosion and flooding, and the rate of environmental change from sea-level rise, loss of shorefast ice2, and melting permafrost are increasing3.

As a retired NOAA research ecologist, I have worked on nature-based solutions (NBS) in the US southeast and mid-Atlantic region. NBS like wetlands, reefs, and islands can reduce risks to coastal communities and provide multiple environmental and socioeconomic benefits4. But, due to differences in physical energy, substrate, and climate, among others, NBS approaches used in more southerly climates are not always transferable to cold regions. For example, there are limited substrate and vegetation options, a shorter seasonal window for construction and vegetation establishment, harsher winters, scouring ice, and a lack of case studies and monitoring data, to name a few.

Given these challenges, what NBS approaches would work in a cold region? And how can we collectively accelerate their use? This is what Jeff King, deputy lead for USACE’s Engineering With Nature® (EWN®) Program, is working to understand. The EWN Program, Cold Regions Work Unit, seeks to fill knowledge gaps on “the use and effectiveness of nature-based solutions in cold regions by supporting new and nontraditional EWN strategies specifically for cold regions like Alaska, Canada, New England, and the Great Lakes.” Since 2017, EWN has been working with Canadian partners like the National Research Council of Canada (NRC) and Coastal Zone Canada Association’s (CZCA) Cold Regions Living Shorelines Community of Practice (CRLS-CoP).

King was invited to share his knowledge of nature-based solutions at the Canada Nature-Based Solutions Event for Cold Regions held June 26–30, 2022, in Halifax, Nova Scotia (NS). “One of our main objectives is to learn and share what techniques work in cold regions and how to adaptively manage to enhance their performance,” explains King. “Given the unique challenges of working in cold regions, exchanging lessons learned through monitoring of case studies, such as the work our Canadian colleagues are doing, is critical to advancing the use of NBS in challenging environments.”

The 5-day event, hosted by the TransCoastal Adaptations Centre for Nature-Based Solutions at Saint Mary’s University and presented in collaboration with NRC and CZCA’s CRLS-CoP, was an opportunity for EWN to broaden international collaborations in cold regions and for our partners to continue developing Canadian Design Guidance, to host a Bay of Fundy Field Trip; and to share case studies, research, and lessons learned across Canada.

The Canada Guidelines Development Effort

The first two days of the event “brought together engineers, scientists and practitioners from Federal, municipal, and First Nations government and academia across Canada” to collaborate on the Nature-Based Infrastructure for Coastal Resilience and Risk Reduction project to develop National Engineering Guidance for Canada. The guidance document, supported by the Canadian Safety and Security Program and led by NRC, builds from where the 2021 USACE-led International Guidelines on Natural and Nature-Based Features for Flood Risk Management leaves off, addressing Canadian-specific shoreline-challenges.

Organized into four regions—Arctic, Atlantic, Pacific, and Great Lakes—it will serve as a guide for municipalities who want to try nature-based solutions.

In 2020, a survey of stakeholders and practitioners across Canada, conducted by NRC as part of a study commissioned by the Canadian Standards Association, cited some reticence within the engineering community as one of the main barriers to NBS implementation5. “It was clear from the feedback we received that we still need to address the knowledge gaps in Canadian design guidance,” said Enda Murphy, Senior Research Engineer, NRC, and a member of the CZCA board of directors with 17 years of coastal engineering, design, consultancy, and applied research experience.

“In Canada, the bulk of coastal protection design is done by engineering consultants usually hired by municipalities, and there is still a reluctance to fully embrace NBS, in part because some engineers don’t see them as tried and tested,” explains Murphy.

Nature-based solutions require working with natural processes. This involves integrating disciplines and different design considerations than for conventional infrastructure. According to Murphy, this is one of the reasons he works with TransCoastal Adaptations and others on large-scale restoration projects. “Case studies can provide the evidence to demonstrate how nature-based designs work and help to bridge the gaps between the engineers, biologists, and other disciplines,” said Murphy.

The design guidance will include evidence from three NBS pilot projects on Canada’s east and west coasts; Metlakatla Shore Protection (New Brunswick, NS), Boundary Bay Living Dyke (Vancouver, British Columbia [BC]), and Chignecto Isthmus (Bay of Fundy, NS).

This was the first in-person meeting of the chapter teams since the effort began in July 2020. Project partners are now working hard to develop the design guidance and to release a draft in advance of the CZCA 2023 conference in Victoria, BC, in June. The guidance document will be updated as the research matures.

Bay of Fundy Field Trip

My favorite part of every conference, the field trip, came on the third day: the Bay of Fundy Field Trip hosted by TransCoastal Adaptations. The purpose was “to explore the changing landscapes of the Bay of Fundy, including natural and human induced changes.: Today, cofounder Danika van Proosdij, coastal geomorphologist and professor at Saint Mary’s University, is tag teaming her guide responsibilities with her cofounding partner of 17 years, Tony Bowron of CB Wetlands and Environmental Specialists (CBWES). In 2018, they co-founded TransCoastal Adaptations, formalizing the existing partnership between Saint Mary’s University and CBWES. TransCoastal Adaptations, Centre of Expertise, is a collaboration among academic, community, government, and industry partners including the Confederacy of Mainland Mi’kmaq.

Decades before nature-based solutions became a mainstream term, van Proosdij was struck with how important the coast is to people in the Maritimes. “Seeing how we are responding to these hazards by using all this rock armoring, I wanted to better understand the tipping points or triggers between marsh accretion and erosion,” says van Proosdij. “If we can understand these dynamics, then we can strategically make them grow and do this on an estuarine scale.”

In 2002, the Saint Mary’s University and CBWES partnership began with habitat mitigation projects for transportation-related construction. Two decades later, their projects have morphed into a climate change adaptation focus. Their largest site to date is a 92-hectare dyke realignment to decrease flooding in Truro, NS. Together, they have restored 161 hectares.

…

Our first stop of the day was the Avon River Causeway, located at the southwestern quadrant of Minas Basin, one of two basins that form the upper reaches of the Bay of Fundy. The Bay of Fundy is famous—in every oceanography book I have ever read—for having the highest tidal range in the world, up to 53 feet (16 meters).6

In the early 1970’s, Causeway construction with a tide gate severed the hydrological connection of an Avon River tributary near Windsor, NS, resulting in rapid establishment of an extensive salt marsh in front of the causeway and a small lake behind. Since 2021, a Ministerial order7 required the tide gates to be opened for a portion of the tide to allow for some fish passage, reconnecting river hydrology and returning the lake to a more natural river state. In 2022, two young Atlantic salmon, known as parr,8 were identified upstream. While a positive outcome for fish, the project is not without controversy given the value some in the local community place on the lake.9

…

In 2018, TransCoastal Adaptations was awarded a 1.2-million-dollar grant to reconnect marsh floodplains in their aptly named “Making Room for Wetlands” project. The goal was to protect communities from the effects of climate change by widening and restoring natural floodplains. This involves moving dykes back to make more room for water. An example of a managed dyke realignment was our next stop.

…

Belcher Street Marsh10 is located on the Cornwallis (Jijuktu’kwejk) River, a tidal river of the Minas Basin. In 2018, approximately 0.8 miles (1.3 kilometers) of dyke protecting 55.8 acres (22.6 hectars) of dykeland (diked marshland) was realigned. We walked single file, very carefully, along the edge of a cornfield to the top of the realigned dyke. Although it had been only 4 years, there was an expanse of lush, nearly shoulder-high intertidal grasses, formerly farm land, that looked like they had been there a millennium.

We treaded single file, deeper into the marsh, to the channel edge bounded by the reddish Bay of Fundy mud. Perched comfortably on the mudflat edge, which was formerly an erosional bend, van Proosdij described their use of inverted root balls, a rock sill, and native vegetation to promote sediment accretion. Stakes used to anchor the inverted root balls, now hidden in the understory of tall grass, were the only evidence of the efforts she described. The marsh recovered quickly in this sediment rich, macrotidal environment. The results are simple and elegant, 100 percent vegetative success in 4 years.

…

Next stop, was a view of Grand Pré, UNESCO World Heritage Site, from Grand Pré View Park. From this vantage point, a quilted landscape stretched below on a semicircular-shaped peninsula jutting into Minas Basin. The landscape was little changed from the mid-eighteenth century when the Acadian diaspora arrived and is still maintained with similar dyke-building technology the settlers used to create farmland out of marsh. Van Proosdij took the opportunity here to describe the physical processes at work for our next stop: Evangeline Beach on the northern shoreline of Grand Pré.

We shuffled off the tour bus down a flight of wooden steps traversing a giraffe-sized rock revetment, protecting an erosional bluff, to stand on the cobble beach below. The revetment parallels the shoreline for the length of five cruise ships, some rocks half the size of a Subaru Outback.

The mudflats of Evangeline Beach and western Minas Basin are a critical feeding area for thousands of shorebirds during the summer.11 But, not this day. It was high tide with nary a shorebird in sight. A ribbon of beach no more than 40 feet paralleled the revetment. Sparse patches of marsh clung to a couple of spots at the water’s edge.

Using her body for scale, van Proosdij stood in front of the revetment and posed this question to the group, her professor hat firmly on. “What kind of nature-based solutions could work in this location?”

I noticed the houses and infrastructure were mere feet from the cliff’s edge. There was evidence of erosion and undercutting at the top of the bluff where a flap of lawn with exposed roots rustled in the wind. Looking to the northeast, straight into the bowels of Minas Basin, was a 31 mile (50 kilometer) fetch. I tried to imagine the wave energy that must punish this shoreline on occasion.

The group enthusiastically shouted “terracing,” “stop mowing,” and other options that didn’t remain in my long-term memory. Van Proosdij responded encouragingly, and I am relieved and surprised by the number of nature-based approaches that could be tried at this challenging, high-energy site. Given my penchant for an unkempt meadow, I am especially intrigued by the idea of “not mowing” to increase resilience.

Helping communities implement NBS to enhance their resilience is what TransCoastal Adaptations is all about. They train students and practitioners to implement nature-based solutions and transform each site into a “living laboratory.” “Where there are community groups who want to do this work, we can write our students into their grants and provide the training communities need,” said van Proosdij, adding, “and sometimes we play ‘the matchmaker,’ helping to bring partners together to get the work done.”

Van Proosdij, sees a bright future for nature-based solutions. “Right now, momentum is building for nature-based solutions, especially with the increased risks of erosion and flooding, and there is a strong need for trained professionals and case studies with monitoring that demonstrate the effectiveness of these approaches.”

After this day of site visits, I was inspired to learn more about NBS in cold regions. Fortunately, there were two more days of knowledge sharing left at the workshop.

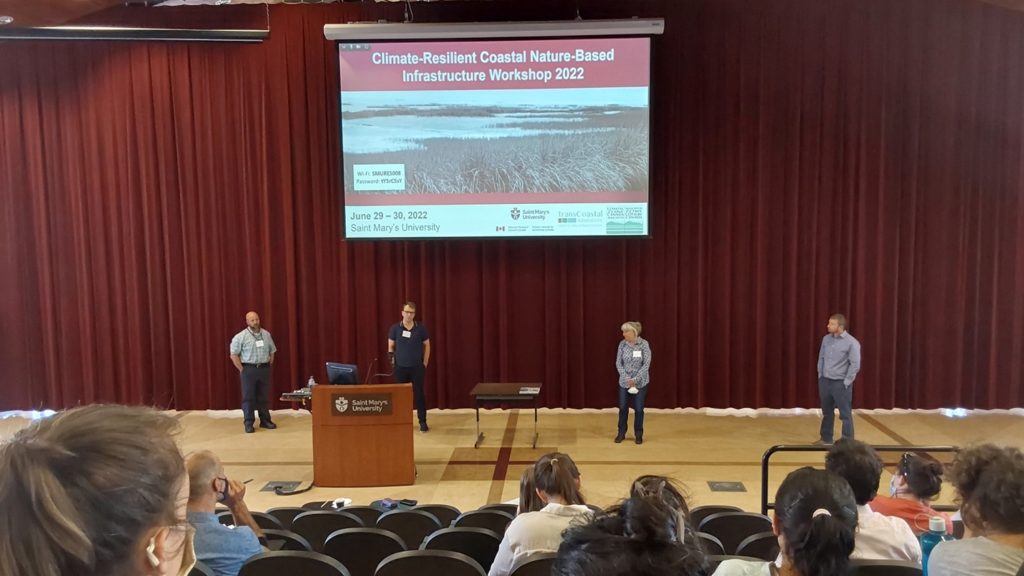

The Workshop

The Climate-Resilient Coastal Nature-Based Infrastructure Workshop, June 29–30, 2022, hosted by TransCoastal Adaptations and the CRLS-COP and held at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax, provided “a forum for engagement, collaboration, critical discourse, and knowledge sharing to advance coastal nature-based solutions and living shorelines research and practice in Canada.”

Jeff King, invited plenary speaker, gave the keynote address for the event where he outlined what is needed to prioritize and accelerate use of nature-based solutions and emphasized Canada’s ongoing role “leading and advancing the practice.”

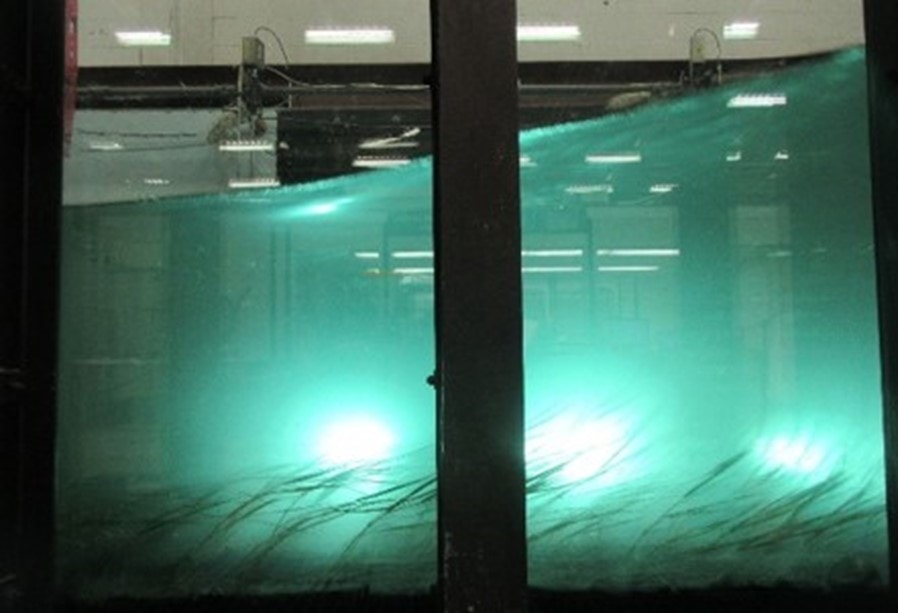

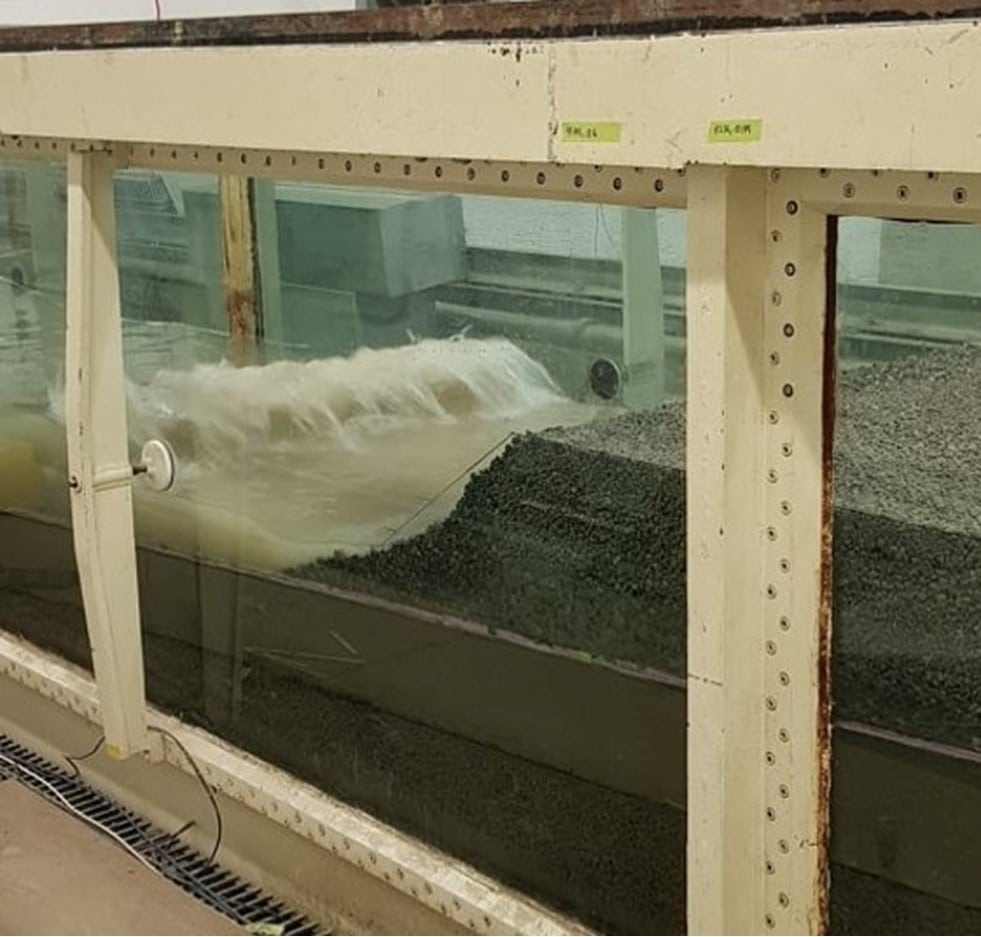

Case studies12 presented at the workshop showcased a range of cold regions restoration techniques and monitoring, many coupled with numerical and physical modeling research. For example, in Metlakatla, BC, a cobble beach and pocket marsh were installed in combination with conventional hard structures (breakwaters) to manage erosion. In the Fraser River Delta, Vancouver, BC, sediment will be used to restore marsh flats and resilience.13 Case studies also included a living dyke in Boundary Bay, Vancouver; dyke realignment in the Bay of Fundy; dune restoration approaches and a sand engine project in support of piping plover habitat on the Acadian Peninsula, New Brunswick; and techniques and lessons learned in erosional bluff restoration—one of my favorites—by the organization Helping Nature Heal Inc. in Nova Scotia.

Participants highlighted the ongoing need for evidence-based case studies with monitoring and funding for adaptive management, including the critical role of vegetation for project success. The need for standards and methods, regulatory efficiencies, and overcoming societal barriers for NBS was also emphasized by participants.

Cold Regions Living Shorelines Community of Practice

Throughout the five-day event, Danker Kolijn, coastal engineer with DHI Water & Environment Inc., highlighted the opportunities for participants to get involved in the CRLS-CoP, whose purpose is to “develop, support, and steward the effective use of living shoreline ideas and principles, in the context of a changing climate, for application in cold regions.”

Danker joined the CZCA Board of Directors in 2016; and in 2018, he volunteered to kick off the CRLS-CoP. “It is a community where people can go to connect across the country and internationally, to exchange ideas, learn from others, and engage in a dialog about the use of nature-based solutions in cold regions,” said Kolijn.

Through Kolijn’s 12 years of experience on living shorelines and design guidance development, he knows there is still work to do to increase the use of living shorelines. “Our big objective is to encourage more members to be involved, to take on leadership roles, and to connect people with a diversity and range of expertise,” explains Kolijn.

“We are building momentum toward the official launch of the regional groups at the CZCA 2023 Conference in Vancouver,” said Kolijn. “Eventually, we also want to get into the advocacy space—to engage in dialogue with all levels of government to highlight the benefits and encourage the use of NBS on heavily populated shorelines.

Four regional chapters are established in the Great Lakes, Pacific, Arctic, and Atlantic. Check out the website if you are interested in joining or leading a regional team or would like more information.

What is Next for EWN and CRLS-CoP in Cold Regions?

“The work being pursued in Canada provides an excellent springboard for integrating learning and best practices into cold regions of the US,” said King. “I am excited to build upon our existing collaborations between the US and Canada on use of NBS in cold regions. To date, our work has led to substantive progress in expanding use of NBS, creating greater resilience, and multipurpose benefits for our nations.”

There will be a special session on EWN in Cold Regions, hosted by the CRLS-CoP, at the 2023 Coastal Zone Canada Conference, in Victoria, BC. This will be the first time that regional chapters will meet in person to share their expertise and experience through case studies, technical presentations, and an interactive workshop format. At the Conference, the CRLS-CoP will chart the vision and objectives for the coming years to increase both membership and impact. You are welcome to join the CZCA, CRLS-CoP, and other EWN practitioners at the CZCA June 11–14, 2023 Conference in Victoria.

Brief Bio

Paula is a retired NOAA research ecologist with 30 years of experience. She has been collaborating with Engineering With Nature® since 2016 and is a co-lead of the Islands chapter in the International Guidelines on Natural and Nature-Based Features for Flood Risk Management. Her interests include research on performance and adaptive management of nature-based solutions and conservation. Connect with her on LinkedIn.

Contacts and Related Links:

- Jeff King, Jeffrey.K.King@usace.army.mil, LinkedIn

- Enda Murphy, Coastal Resilience Technology Theme—NRC, LinkedIn

- Danika van Proosdij, dvanproo@smu.ca, www.transcoastaladaptations.com

- Danker Kolijn, dank@dhigroup.com, LinkedIn

- CZCA Conference 2023: Connecting Canadians with our Coast, 11-14 Jun 2023

References

1. Shen HH (2015) Cold Regions Science and Marine Technnology. Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS). Clarkson University, Potsdam, NY. Available at https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C33&q=Hayley+H.+Shen+Cold+regions+science+and+marine+technology+citation&btnG=.

2. Stacey K, Smith LC, Horvat C, Pearson B, Dale B and Lynch AH (2020) Arctic ‘shorefast’ sea ice threatened by climate change, study finds. Brown University, Providence, RI. Available at https://www.brown.edu/news/2020-05-04/shorefast.

3. Government of Canada (2019) Melting Glaciers, Rising Sea Levels, Thawing Permafrost and Unpredictable Groundwater Levels: The Unsettling Effects of Climate Change. Available at https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/simply-science/melting-glaciers-rising-sea-levels-thawing-permafrost-and-unpredictable-groundwater-l/21842.

4. Whitfield PE, Suedel BC, Egan, KA, Corbino JM, Davis JL, Carson DC, Tritinger AS, Szimanski DM, Balthis WL, Gailani JZ, King JK (2022) Engineering With Nature® principles in action : islands. ERDC TR-22-9. Engineer Research and Development Center (U.S.). Available at https://hdl.handle.net/11681/44940.

5. Vouk I, Pilechi V, Provan M, Murphy E (2021) Nature-Based Solutions for Coastal and Riverine Flood and Erosion Risk Management. Canadian Standards Association, Toronto, ON. Available at https://www.csagroup.org/article/research/nature-based-solutions-for-coastal-and-riverine-flood-and-erosion-risk-management/.

6. NOAA (2022) Where is the highest tide? National Ocean Service website. Available at https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/highesttide.html.

7. Morris-Underhill C (2021) West Hants officials to meet with DFO over Avon River flow. SaltWire Network. Atlantic, Canada. Available at https://www.saltwire.com/atlantic-canada/news/west-hants-mayor-cao-meeting-dfo-rep-to-hash-out-windsor-causeway-concerns-100592206/#:~:text=In%20March%2C%20DFO%20issued%20a,minutes%20to%20allow%20fish%20passage.

8. Copeland T (2022) Parr: a funny word biologists use to describe young salmon and trout. FishingWire. Available at https://thefishingwire.com/parr-a-funny-word-biologists-use-to-describe-young-salmon-and-trout/.

9. Beswick A (2021) Jordan orders gates opened on Avon River to allow fish passage. SaltWire Network. Nova Scotia. Available at https://www.saltwire.com/nova-scotia/news/jordan-orders-gates-opened-on-avon-river-to-allow-fish-passage-566829/.

10. Manuel P, Rapaport E (2021) Belcher Street Marsh Dyke Realignment and Tidal Wetland Restoration Project: A Case Study of Nature-based Coastal Adaptation in Nova Scotia. School of Planning, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia. Available at https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5c83d5c63560c33561cc74de/t/61aeca0bf994d4620c5aba87/1638844941547/MRfM_BelcherStMarsh_Case_Study_Final__Dec_05_21_Updated.pdf.

11. SaltWire (2017) Shorebirds are here for a special viewing at Evangeline Beach. SaltWire Network. Atlantic, Canada. Available at https://www.saltwire.com/atlantic-canada/federal-election/shorebirds-are-here-for-a-special-viewing-at-evangeline-beach-72055/.

12. Climate-Resilient Coastal Nature-Based Infrastructure Workshop (2022) Book of abstracts. Saint Mary’s University Halifax, Nova Scotia, June 29-30, 2022. Available at https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5c83d5c63560c33561cc74de/t/62bc9fed00acfc4cb05236dc/1656528879401/Book+of+Abstracts+-+Climate-Resilient+Coastal+Nature-Based+Infrastructure+Workshop+2022.pdf.

13. Lewis A (2022) Ducks Unlimited Canada releases comprehensive report to guide future restoration efforts in the Fraser River Estuary. GlobalNewswire. Available at https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2022/03/31/2414213/0/en/Ducks-Unlimited-Canada-releases-comprehensive-report-to-guide-futu