California’s landscape is big and diverse. When I moved to the East Coast in 1988, I seemed to encounter a lot of people who held what I called the “surfing and earthquakes” image of California, a view of the state that is dominated by images of southern California beaches combined with tectonic disaster. I’ve also met many people who attempted to cover too much ground on their first visit to the state and left impressed by California’s enormity and diversity. California is the third largest state in the country, covering >150,000 square miles that includes the tallest mountain (Mt. Whitney, 14,494 feet) and the lowest spot (Death Valley, 282 feet below sea level) in the contiguous 48 states.

The more than 800 miles of coastal landscape between the northern and southern border of California is both diverse and beautiful. I will enthusiastically declare my personal preference for the Central Coast of California, where I’ve spent a lot of time, and particularly for Monterey Bay. The fertile landscape around Monterey Bay was the setting for much of John Steinbeck’s writing, including development of its agriculture and the social tensions present during the first half of the 20th century. On a recent trip to California, I had the opportunity to visit a flood risk management project in the Monterey Bay area adjacent to the city of Watsonville and the town of Pajaro. Watsonville and the neighboring community of Pajaro have a population of about 50,000 with more than 80% having Hispanic or Latino heritage. About 20% of the population lives below the poverty line—the median annual income in the unincorporated town of Pajaro is $22,000. Agriculture is a major part of the local economy and labor market.

As the energy of the California Gold Rush declined in the latter part of the 19th century, California’s agricultural boom began. The number of farms in California increased by 560% between 1869 and 1929 to a total of 136,000. In addition to the San Joaquin Valley, the land around Monterey Bay is both agriculturally productive and profitable, producing a broad array of fruits and vegetables. Neighboring Castroville lays claim to being the artichoke capital of the world—a delicious but odd looking plant, to be sure.

The Pajaro River owes its name to the Portola expedition in 1769 when Spanish soldiers reported seeing a large bird near the river (Rio del Pajaro, River of the Bird). The Pajaro begins at San Felipe Lake and travels some 30 miles through Watsonville to Monterey Bay. The tributaries of the Pajaro reach into the Diablo Range and San Benito Mountain. California’s famous (or infamous) San Andreas Fault cuts across the watershed and is responsible for historical changes in the river’s path. The Loma Prieta earthquake in 1989, which interrupted a game of the World Series that year, had its own impact on the Pajaro levee system.

Flooding has plagued the communities around the Pajaro River through numerous events over more than 100 years. The US Army Corps of Engineers constructed a system of levees on the river in 1949, but flooding has continued to be a challenge for Watsonville, the town of Pajaro, and area farms. Today, the Pajaro levee system provides only an 8-year level of flood protection to the surrounding communities, among the lowest of any federal flood control system in California (translation, there is a 12.5% probability of a flood along the system in any given year). Particularly damaging floods in 1995 (which resulted in two deaths), 1997, and 1998 (which resulted in a Presidential disaster declaration) produced $10s of millions in economic damage.

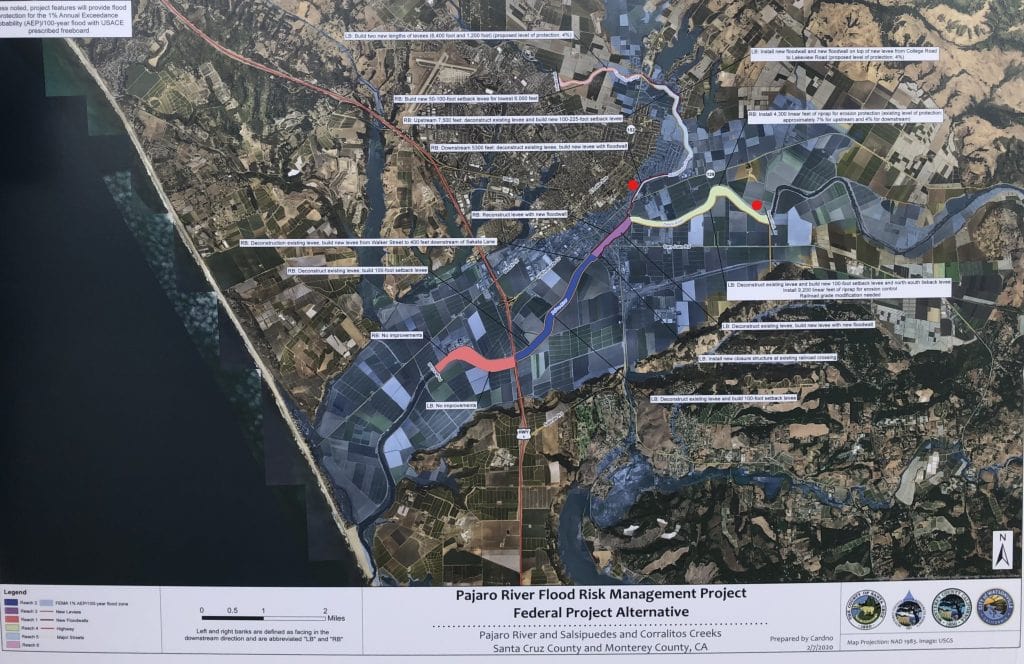

A new project on the Pajaro River has been undertaken by the US Army Corps of Engineers and its partners in Monterey and Santa Cruz Counties (the river forms the border between the counties), to identify long-term solutions. I was invited by the project team to visit the project and to consider, with them, the opportunities to incorporate Engineering With Nature principles and practices. One of the greatest opportunities to incorporate EWN into a flood risk management project is the use of setback levees, a realignment of levees that creates more space for the river and water. The team took me to a few locations where setbacks are being considered. In this river system, setback levees will help restore the coastal watershed by reconnecting historic floodplains to the river system, promoting a more dynamic and ecologically diverse river system, while achieving flood risk reduction goals by providing the space for the river and water to spread out and slow down (see Stop #6 on the Heartland Tour for highlights on 3 levee setbacks along the Missouri River). Another benefit of spreading out and slowing down water over the landscape is to support groundwater recharge—a very significant benefit in this overdrawn valley—which has broad relevance across California and other regions pursuing water resilience in the face of drought, climate change, and completing water uses.

I was struck by the collaboration that is taking place, which is a key element of applying Engineering With Nature in projects across the country, to achieve sustainable solutions. The Pajaro River forms the boundary between two counties, but as we have learned, water knows no bounds. Rather than working at cross purposes, the two counties are actively collaborating through funding, outreach, and new governance structures to come up with a watershed-scale solution that benefits communities on both sides of the river.

What I saw that day in Watsonville, and the opportunities we discussed, highlight an important aspect of Engineering With Nature’s general applicability and relevance. Nature can, if we let it, contribute to enduring solutions at a range of different scales, from “beasts” like the Sacramento River (or the Mississippi and the Missouri) to rivers like the Pajaro. Rivers of all sizes have a persistent way of forcing their “will” upon human interests. The art of engineering is to seek out an enduring balance between natural forces and processes and the people and communities occupying the landscape, and to do so in a way the produces, for generations, an equitable balance of economic, environmental and social benefits for the whole community.