I lived the first 25 years of my life in the San Joaquin Valley of California. On December 1st, 2021, I saw the valley as I had never seen it before. Gary Lippner (Deputy Director for Flood Management and Dam Safety) and Kris Tjernell (Deputy Director for Integrated Watershed Management) with the California Department of Water Resources and I boarded a helicopter at a small airfield in Lodi, California at the northern edge of the San Joaquin Valley. We flew south for 2 hours to Bakersfield at the southern end of the valley (about 240 ground miles) and collected two more passengers, COL Toni Gant, the Commander of the USACE South Pacific Division, and Cheree Petersen the Program Director for SPD, who had been to Lake Isabella on the Kern River the day before to tour USACE’s Isabella Lake dam safety modification project. A lot of thoughts passed through my mind that day as we observed and talked about the valley, water infrastructure, challenges, and the future. I thought about my quarter-century of living in the valley, what the natural landscape was like before human engineering, about the combination of prosperity and adversity in the valley, and what the valley’s landscape could become in the future.

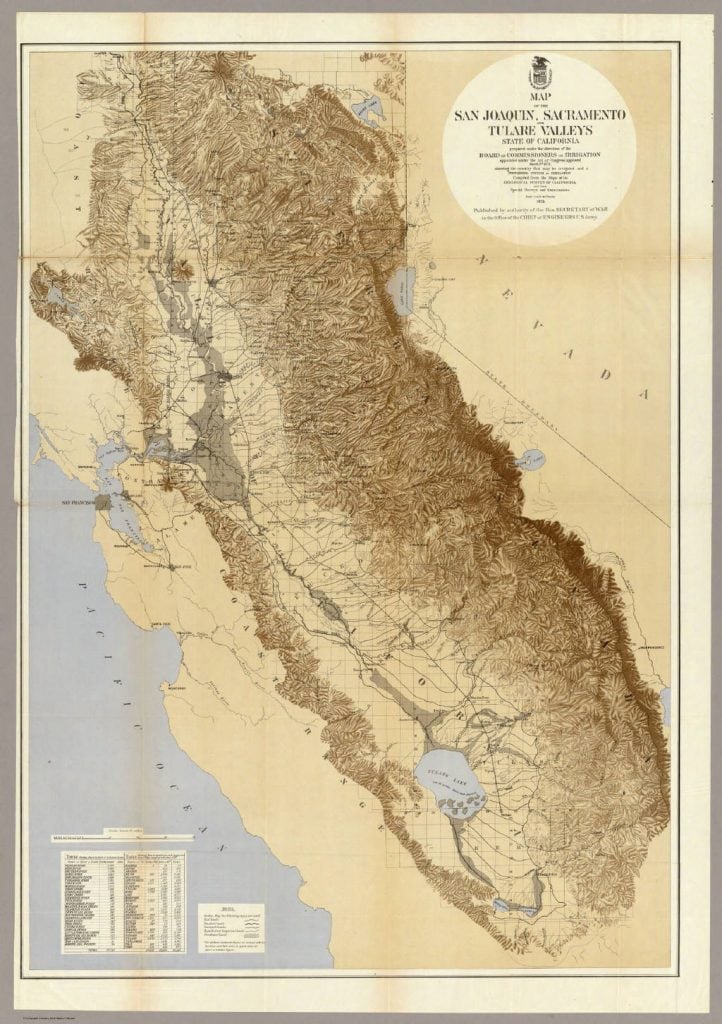

The great Central Valley of California is about 450 miles long and 50 miles wide. The northern and southern portions of the valley, the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys, are named after their dominant rivers.

Pedro Fages and his company were the first Europeans to visit the San Joaquin Valley. From the recorded accounts, Fages appears to have led two separate expeditions into the San Joaquin Valley in 1772, exploring both the northern and southern portions of the valley. Fages and Francisco Palou documented what they saw. In the north, they saw the point at which the San Joaquin river meets the great San Francisco estuary.

“The [San Joaquin] which discharges into the estuary of that name is more than 120 leagues in length, in places fifteen to twenty in width, and it winds through a plain which is a labyrinth of lagoons and tulares. The plain is thickly peopled, having many large rancherias; and abounds in grain, deer, bears, geese, ducks, cranes; indeed, every kind of animal, terrestrial and aerial.” In the south “he saw a great plain and in it some immense tule marshes, with many large lakes from which, judging by their direction, he infers that those rivers (the San Joaquin and its affluents) are formed…” (These and other accounts are recorded in Wallace Smith’s wonderful history of the San Joaquin Valley, Garden of the Sun.)

The arrival of the Spanish, other Europeans and eventually the newly organized Americans transformed California’s landscape. The discovery of gold in the rivers and streams of the Sacramento Valley and foothills in 1849 and the industrialization of gold extraction through hydraulic mining accelerated the transformation. The period of intense mining was followed by a more significant and long-lasting transformative agent: large-scale agriculture.

California has the largest overall economy in the United States. The state also leads the nation in agricultural productivity, with $50 billion in annual farm-level sales, nearly twice the sales of the second position. The Golden State produces over one-third of all vegetables and two-thirds of all fruits and nuts in the country and generates about 12% of total U.S. agricultural sales. Within California agriculture, the San Joaquin Valley leads the way. In 2015, the total value of the 250 varieties of agricultural commodities grown in the 8 counties of the valley was >$34 billion. The San Joaquin Valley encompasses 27,000 square miles, of which nearly 8,000 square miles (roughly 5,000,000 acres) is farmland. About 4 million people live in the San Joaquin Valley. The median household income in the valley is $50,000, but nearly 25% of the population lives below the poverty line, a measure of social vulnerability in an agricultural “land of plenty”. Annual rainfall across the San Joaquin Valley ranges between around 5 inches in its southern reaches to about 20 inches in the north. The valley’s prodigious agricultural engine runs on irrigation water.

The first irrigation canal in the San Joaquin Valley tapped into Kings River near Centerville in 1868. Over the next 100 years, thousands of miles of irrigation canal would crisscross the valley and in combination with large dam and reservoir projects in the mountains, foothills and valley would transform the natural landscape into an artificial agricultural powerhouse (irrigation canals—with their frogs, tadpoles, minnows, and water striders—provided me with my first exposure to aquatic ecology as a child). Today, 6 of the 8 counties in the San Joaquin Valley are among the top 10 agricultural producers in the United States, with Fresno County holding the top position with nearly $8 billion in farm-level sales in 2018.

There are about 24 million acres of land devoted to farming and ranching in California, of which about 9 million acres are irrigated. The two large water systems, the Central Valley Project and the State Water Project move on the order of 10 million acre-feet of water across the state, predominantly from north to south. Dams, reservoirs, levees, canals, pumps, tunnels and pipelines associated with the major rivers—including the Kern, Kaweah, Tule, Kings, and San Joaquin Rivers—were the tools used to transform the San Joaquin Valley. Before these tools were applied, Tulare Lake at the southern end of the San Joaquin Valley was the largest lake west of the Mississippi River, reaching more than 800 square miles during wet periods. In the 1800s, one could travel across Tulare Lake on a steamboat. Seventy thousand pounds of fish were harvested from the lake in one 3-month period in 1888 and shipped to market in San Francisco.

The lake served as a significant stop-over point on the Pacific Flyway for millions of migrating birds. Tulare Lake was erased from the valley’s landscape by the middle of the 20th century in the name of flood control, development and agriculture. The lakebed was planted in cotton that stretched as far as the eye could see.

Of the roughly 30 million acre-feet of annual precipitation that is allocated to agriculture in California, 60% is consumed within the San Joaquin Valley. The development of agricultural land in the San Joaquin Valley over the decades has outpaced the ability of the two statewide water projects to deliver water. Private groundwater wells, installed by farmers and agribusiness by the thousands in recent decades, are chasing ancient groundwater deeper and deeper into aquifers (beyond 2,000 feet) to make up the difference. Climate change and intensified periods of drought are exacerbating the problem that germinated from an unfortunate combination of misaligned incentives and inadequate policy.

The pumping of millions of acre-feet of groundwater has caused significant land subsidence in the San Joaquin Valley (as much as 30 feet in portions of Kern County) and has, ironically, created additional engineering challenges for water infrastructure, including for the California Aqueduct and levee maintenance. The passage of California’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act in 2014, which mandates the development of groundwater management plans across the state, is expected to bring about another period of transformation in the valley in coming decades, both in agriculture and the landscape.

Landscape transformation was foremost in my mind as we flew over the San Joaquin Valley on a warm, sunny December day. It’s difficult for me to wrap my mind around how much the valley’s landscape has changed in 100 years, and more change is coming. Today’s and tomorrow’s climate cannot be reconciled with current practices in the valley and its landscape. But I believe that nature provides a source of hope for the valley’s future. A new balance could be achieved by resurrecting natural features and processes that were “engineered-out” of the valley in the 20th century. Applying the principles and practices of Engineering With Nature could provide the means to realign the social-ecological system for enduring sustainability, water and social resilience, and to produce the diversity of benefits and values that nature can provide.