The Sacramento is a “beast” of a river. It runs 400 miles from Mount Shasta to the delta where it meets up with its southern sister at the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, as both rivers join with the San Francisco Estuary and Bay. The Sacramento River drains a watershed encompassing 26,000 square miles. Gabriel Moraga gave the river its current name, Rio de los Sacramentos, in 1808. Before dams and impoundments were constructed in the watershed, peak discharges during the wet season are estimated to have reached 650,000 cubic feet per second (cfs), which is second only to the Columbia River on the Pacific Coast of the United States, and is comparable to annual average discharges on country’s largest river, the Mississippi. Consistent with California’s climate, the Sacramento’s flow during dry periods can drop below 1,000 cfs. But it’s during periods of high flow when the Sacramento River has left its marks on California’s landscape and history.

The great flood of 1862 began with the arrival of rain and snow in December, 1861 that continued across the state for weeks, in combination with unseasonably high temperatures that melted the snow. The event was undoubtedly driven by what today is called an atmospheric river that carries moisture-laden air from across the Pacific Ocean. During the event, Los Angeles received more than 35 inches of rain in one month, the equivalent of more than 2 years of average annual rainfall. At first, people across the state must have welcomed the rain with the hope that it signaled the end to a 20-year period of drought in the region. That hope was transformed into despair as the disastrous flooding unfolded. Flooding in the Central Valley was dramatic and devastating. The inundation stretched along the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys and covered an area that was 300 miles long and 20 miles wide; in some places the water was 30 feet deep, covering telegraph poles. An estimated 3-3.5 million acres of land was flooded, including thousands of farms. Nearly a million sheep and cattle were killed by the flood.

About 300,000 people came to California during the Gold Rush after the precious metal’s discovery in 1849 along the American River (a tributary of the Sacramento), quadrupling the state’s population. The California State Legislature moved to Sacramento in 1854 and by the 1860s the city’s population had reached 10,000. The city’s streets became a network of canals during the flooding. The states newly elected eighth governor, Leland Stanford, traveled to his inauguration on January 10th in a rowboat. The flooding was exacerbated by millions of tons of sediment and debris that had been deposited in the Sacramento, Feather and American Rivers as a result of hydraulic mining for gold. The human toll of the flooding was considerable. An estimated 4,000 people, 1% of the state’s population, were killed by the flooding.

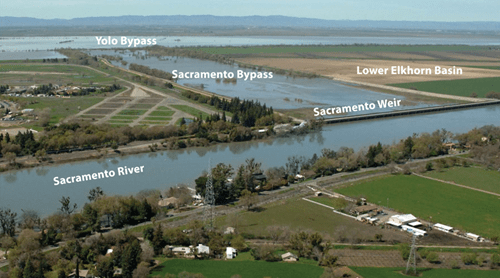

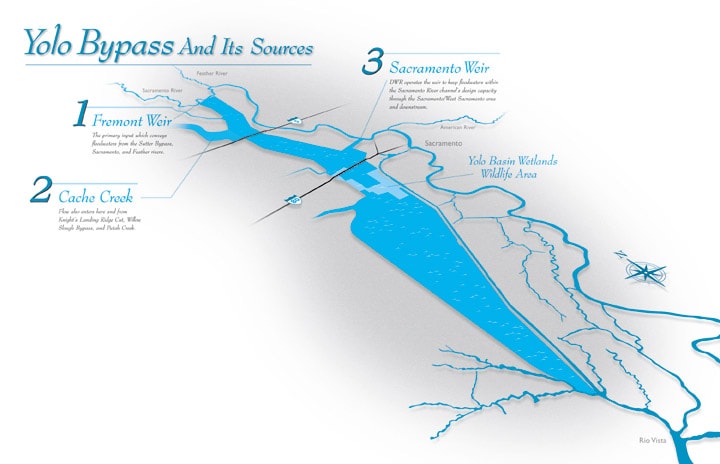

Well before 1862, and most definitely after, solutions for taming the Sacramento River to “control” flooding received considerable attention. For years, the prevailing approach was to build bigger and better levees, but increasing attention was being given to allocating more space to the rivers’ high flows. In 1880, William H. Hall, the California State Engineer, recommended such a comprehensive flood plan. Several more floods occurred in the watershed in the closing decades of the 19th century and into the 20th. In 1916, the Sacramento Weir was constructed on the river, the first of several that would be constructed, that would divert water from the river’s main channel onto land allocated to receive that water, so-called bypasses, thus reducing water levels and relieving pressure within the main channel. In 1917, Congress authorized the Sacramento Flood Control System that provided federal involvement and support, through the US Army Corps of Engineers, to implement the plan envisioned by Hall, which combined strengthened levees with the plan’s main feature and innovation: the system of weirs and bypasses. The central element and largest feature of the system is the Yolo Bypass.

I had the opportunity to visit the Sacramento Weir and the Yolo Bypass on the 2nd and 3rd of December, 2021 and to see and hear how the engineering, environmental, and social elements of the system come together in what is one of the country’s oldest nature-based solutions for flood risk management.

The Sacramento Weir is a 1,920-foot- long concrete structure along the right (west) bank of the river. A construction project is currently underway that will add another 1,500 feet to the weir (expanding its capacity to divert high flows) and will include a 2-mile-long setback levee that will provide more space for the river, the product of long-term collaborations and partnerships. The Yolo Bypass that receives diverted water encompasses >59,000 acres of land. Seventy-five percent of the land within the bypass is privately owned farmland incorporated within the bypass through easements, a significant example of coordination and partnering across the public and private sectors that is necessary for large-scale flood risk management. The Yolo Bypass can take up to 80% of the flood flows from the Sacramento, Feather and American Rivers.

There are many aspects of the Yolo Bypass that demonstrate its inspiring, multi-purpose nature. One of the most visible of these aspects is the Yolo Bypass Wildlife Area. This wildlife area covers >16,000 acres in the bypass, land managed for flood waters, agriculture, and wildlife. I drove 20 minutes from downtown Sacramento to visit the wildlife area. It was a beautiful morning that began with a light shroud of fog that evolved into a warm, sunny day, a wonderful backdrop to experience the calm beauty of the restored wetland. On this weekday morning, I saw dozens of visitors to the wildlife area equipped for bird watching with binoculars and cameras; there are a lot of birds to see during this season of migration on the Pacific Flyway. I saw several species of birds: waterfowl, songbirds, and several raptors that included a persistent Northern Harrier (Marsh Hawk) that flew low over the marsh grass and periodically hovered above the stems in search of prey in its own impersonation of a predatory hummingbird. President Bill Clinton dedicated the area in November of 1997 and identified the project as a national model in “trying to improve our economy and lift our standard of living while improving, not diminishing, our environment.” The Yolo Bypass Wildlife Area is managed by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and receives thousands of recreational visitors annually.

Flood risk management can and should include nature as a part of the solution. There are abundant examples of such integration in projects across the United States and around the world. These projects have provided ample opportunity to learn lessons from nature and hone our experience at expanding the diversity of benefits and value that can be achieved through such multi-purpose approaches to hazard mitigation and risk management. The trillion dollars of public funding being invested through the 2021 Infrastructure Investments and Jobs Act demonstrates Congress and the Administration’s support for such integration. For example, of the $5 billion allocated to USACE for inland and coastal flood risk management, $1.75 billion was directed toward multi-purpose projects. The question I invite you to ponder is why multi-purpose projects seem to be the exception rather than the rule? Surely, producing more project benefits and more diverse benefits makes for good policy and sound public investment. Some careful, thoughtful reader might respond, “Yes, but at what cost? The goal should be to produce project value, i.e., total benefits minus total costs.” To which I might respond, “If only we evaluated the total economic, environmental and social benefits and costs of infrastructure projects! Then we would surely be on the road to Engineering With Nature everywhere!”

The Yolo Bypass has been producing a diverse array of economic, environmental, and social benefits for many decades, and I’m persuaded that the potential exists to expand these benefits in the future. I’m also persuaded that the overall approach, and the lessons that a 100-year-old nature-based solution can teach, should be applied across the United States and elsewhere, even at larger scales, to achieve enduring resilience.